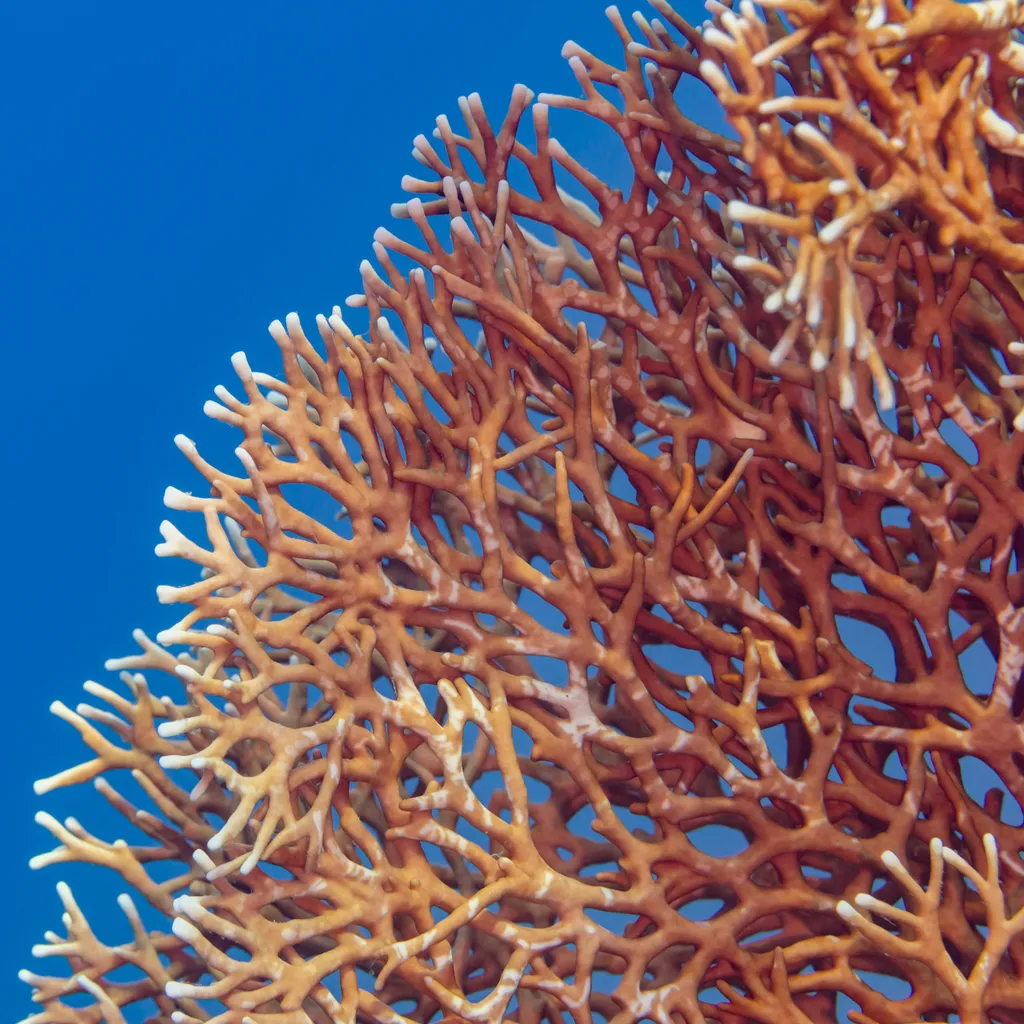

Fire Coral(wire coral)

Millepora (main fire coral genus)

Photo by Diego Delso / CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Fire corals are the ultimate reef prank: they look like true corals, build solid limestone skeletons, and often grow right next to branching Acropora—yet they're actually hydrozoans, closer relatives of hydroids and some jellyfish. To divers, they can be beautiful or brutal depending on how close you get. From a distance, fire corals form golden plates, blades, and antler-like branches that catch the light on wave-battered reef crests. Up close—or worse, on bare skin—they deliver one of the reef's most memorable lessons: never grab the pretty yellow stuff. Tiny stinging polyps hide in pores on the surface, armed with nematocysts potent enough to leave red welts and a burning sensation that can last for hours. But fire corals are more than underwater booby traps—they're important reef framework builders in high-energy zones, creating habitat for fishes and invertebrates where few other corals can survive. Once you learn to recognize them, they become a key piece of the reef puzzle rather than a painful surprise.

🔬Classification

📏Physical Features

🌊Habitat Info

⚠️Safety & Conservation

Identification Guide

Photo by Diego Delso / CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Not a True Coral: Hard, calcareous skeleton like stony corals, but taxonomically a hydrozoan (Millepora)

- Growth Forms: Plates, blades, boxy mounds, encrusting sheets, and antler-like branching fingers

- Color: Typically yellow, golden, tan, or orange; actively growing tips are often pale or white

- Surface Texture: Smooth to the eye but dotted with tiny pores (dactylopore and gastropore openings) instead of visible polyps

- Location: Common on high-energy reef crests, drop-off edges, and channel mouths exposed to waves and strong currents

- Branch Profile: Branches often have squarish or flattened cross-sections, with blunt, sometimes upturned tips

- No Obvious Polyp Heads: Unlike Acropora, no distinct corallites; surface looks more uniform and "waxy"

- Pain Test (Don’t Use!): A strong, delayed burning sting after contact is a classic fire coral signature—identify visually, not by touching

Top 10 Fun Facts about Fire Coral(wire coral)

Photo by Derek Keats / CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

1. Coral in Disguise: A Hydrozoan, Not a Scleractinian

Fire corals fool almost everyone at first—including many new divers and even some photographers—because they build hard skeletons just like true stony corals. But taxonomically, they belong to the class Hydrozoa, not the stony coral order Scleractinia. Their colonies are composed of two main polyp types: gastrozooids for feeding and dactylozooids for defense, housed in different pore types on the skeleton. The resemblance to branching or plating hard corals is a prime example of convergent evolution—different lineages evolving similar engineering solutions (a rigid, wave-resistant skeleton) to survive on high-energy reef crests.

2. The Burn Behind the Name

Fire corals get their name from the intense burning sensation they cause when skin brushes against them. Their nematocysts are concentrated in the dactylozooids, which extend slightly from tiny pores on the surface. Contact can deliver enough venom to cause immediate stinging, followed by red welts, swelling, and itching that may last for hours or even days. For most divers, the sting is painful but not dangerous, though allergic reactions are possible. Rubbing or scratching spreads the nematocysts and makes things worse. The best treatment is to rinse with seawater, carefully remove any remaining tissue, apply vinegar or specific sting treatments if recommended locally, and avoid freshwater or alcohol initially, which can trigger unfired nematocysts.

3. Wave Zone Specialists

Fire corals are specialists of the surf zone, thriving where waves and currents are too strong for many delicate corals. Their robust skeletons and encrusting-to-branching forms let them absorb and dissipate wave energy without breaking. By colonizing reef crests, ridges, and channel mouths, they help stabilize the reef framework and create complex three-dimensional habitat in some of the harshest shallow-water environments. For reef fish and invertebrates, fire coral thickets are both shelter and feeding grounds; for divers, they mark some of the most dynamic and visually dramatic parts of the reef—and the places where good buoyancy and situational awareness matter most.

4. Hidden Polyps and Double Pores

Unlike many showy corals where individual polyps are obvious, fire corals hide their polyps inside the skeleton, exposing only small openings. Each colony surface is dotted with two main pore types: gastro-pores, where feeding polyps extend to capture plankton, and dactylo-pores, where defensive polyps emerge to sting potential threats. Under magnification, these pores give the surface a distinctive pattern that taxonomists use to separate species. To the naked eye, this micro-architecture translates into a slightly pitted or porous look, especially visible on branch sides and plate faces. Learning to recognize this subtle texture is one of the best ways for divers to distinguish fire coral from harmless lookalikes.

5. Color Clues and Lookalikes

Many fire corals are golden-yellow to tan, often with paler or white tips on actively growing edges. This color, combined with the habitat (wave-battered reef crests), makes them easy to confuse with branching Acropora or plating Montipora for inexperienced eyes. But there are key differences: fire coral surfaces are smoother, with tiny pores instead of clear corallites; branches often have squarer cross-sections; and the tissue can appear thinner and more "waxy". Some sponges and encrusting algae can also mimic their color from a distance. For divers, the rule is simple: on a high-energy reef crest, if it's yellow, rigid, and you aren't 100% sure what it is, don't touch it.

6. Symbiosis and Reef Real Estate

Like many reef organisms, fire corals often host small commensals: crabs, shrimps, and tiny fish may shelter among the branches, taking advantage of the stinging protection. Some damselfish hover just above fire coral patches, darting into the branches when threatened. Algae and other sessile organisms may colonize dead portions of the skeleton, while living tissue continues to expand elsewhere. Competition for space with hard corals, sponges, and algae is intense on reef crests, and fire corals use both physical overgrowth and stinging polyps to claim territory. Their presence can influence which other species dominate a particular patch of reef.

7. Reproduction: Medusae and Planulae

As hydrozoans, fire corals have a life cycle that includes both polyp and medusa stages, though the medusae are tiny and rarely noticed by divers. Gastrozooids within the colony produce medusae that are released into the water column, where they spawn and produce fertilized eggs. These develop into planula larvae that drift with currents before settling on suitable hard substrate and metamorphosing into new polyps. The new colonies initially grow as encrusting sheets before developing blades or branches. This combination of sexual reproduction (via medusae and larvae) and asexual expansion (by colony growth) allows fire corals to rapidly colonize prime wave-exposed habitats when conditions are right.

8. Fire Coral and Bleaching

Fire corals, like many reef cnidarians, often host symbiotic zooxanthellae that contribute to their golden-brown coloration and energy budget. Under thermal stress, they can undergo bleaching, expelling these algae and turning pale or white. Bleached fire coral colonies are more vulnerable to disease and physical damage, and prolonged bleaching can lead to partial or total colony death. Some studies suggest that fire corals may be slightly more tolerant of heat stress than some delicate stony corals, but repeated marine heatwaves still take a toll. For divers, seeing white, skeletal fire coral patches where golden blades once stood is a sobering sign that climate change is impacting even the toughest inhabitants of the surf zone.

9. First Aid and Myth-Busting

Fire coral stings have spawned plenty of dive boat stories and questionable remedies. Common myths include using fresh water, alcohol, or urine—all of which can make things worse by triggering unfired nematocysts. Evidence-based first aid focuses on rinsing with seawater, carefully removing any visible coral or tissue, and then using vinegar or specific sting solutions when appropriate to inactivate nematocysts (local protocols vary). Hot-water immersion can help relieve pain for many marine stings, but should be done cautiously and within recommended temperature ranges. The best cure, of course, is prevention: full suits, good trim, and the habit of never grabbing anything on the reef unless you absolutely must—and even then, choosing non-living rock with care.

10. Training Your Eye (and Keeping Your Skin)

For new divers, fire coral encounters are almost a rite of passage—a small tax paid in stings for learning reef awareness. But it doesn't have to be that way. By deliberately training your eye to recognize fire coral forms—golden plates, square-tipped branches, smooth porous surfaces in high-energy zones—you can dramatically reduce your odds of painful contact. Instructors can use fire coral as a teaching tool: pointing it out on briefings and shallow dives, explaining how it differs from harmless corals, and emphasizing the "look, don't touch" ethic. For photographers, understanding fire coral means knowing where not to brace a hand or strobe arm when composing shots on surge-swept ridges. In short, fire coral is both a hazard and a teacher—once you learn its lessons, you become a much more competent and reef-friendly diver.

Diving & Observation Notes

Photo by jon hanson from london / CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

🧭 Finding Fire Corals

- Wave-Exposed Zones: Focus on reef crests, outer ridges, and channel mouths where waves break.

- Color and Shape: Scan for yellow–golden plates, blades, and square-tipped branches among other corals.

- Depth Band: Most common between 1–15m, especially where surge and light are strongest.

- Context Clues: Areas with surge channels, breaking waves, and strong surface chop are classic fire coral habitats.

🤿 Behavior & Observation

- Flow Interaction: Watch how fire coral colonies deflect and buffer waves, often at the very edge of the reef.

- Competition: Note how they overgrow or border other corals and sponges, carving out territory.

- Condition: Compare healthy golden colonies with pale or algae-covered patches that may indicate damage or past bleaching.

📸 Photo Tips

- No Contact: Compose shots without bracing on the reef—use mid-water positioning or dead rock far from living tissue.

- Texture: Side lighting brings out the subtle pore patterns and branch edges.

- Context Shots: Include breaking waves or reef crest in the frame to show their high-energy habitat.

- Color Control: Yellow and white tips blow out easily—slightly underexpose and recover midtones in post.

⚠️ Safety & Ethics

- Do Not Touch: Treat all yellow, rigid reef structures in high-energy zones as potentially stinging.

- Skin Coverage: Wear full suits and gloves where legal and appropriate to reduce sting risk.

- Anchoring & Lines: Avoid tying ropes directly to living reef—fire corals and other organisms are easily damaged.

- Education: Brief new divers on fire coral ID and sting avoidance as part of entry-level training.

🌏 Best Locations

- Red Sea: Abundant fire coral on shallow reef crests and drop-offs.

- Caribbean & Bahamas: Common on outer reefs and surge channels.

- Indo-Pacific Reef Crests: High-energy outer slopes often lined with fire coral plates.

- Great Barrier Reef: Reef-flat and crest zones with mixed hard coral and fire coral communities.

Best Places to Dive with Fire Coral(wire coral)

Raja Ampat

Raja Ampat, the “Four Kings,” is an archipelago of more than 1,500 islands at the edge of Indonesian West Papua. Its reefs sit in the heart of the Coral Triangle, where Pacific currents funnel nutrients into shallow seas and feed the world’s richest marine biodiversity. Diving here means gliding over colourful walls and coral gardens buzzing with more than 550 species of hard and soft corals and an estimated 1,500 fish species. You’ll meet blacktip and whitetip reef sharks on almost every dive, witness giant trevally and dogtooth tuna hunting schools of fusiliers, and encounter wobbegong “carpet” sharks, turtles, manta rays and dolphins. From cape pinnacles swarming with life to calm bays rich in macro critters, Raja Ampat offers endless variety. Above water, karst limestone islands and emerald lagoons provide spectacular scenery between dives.

Maldives

Scattered across the Indian Ocean like strings of pearls, the Maldives’ 26 atolls encompass more than a thousand low‑lying islands, reefs and sandbanks. Beneath the turquoise surface are channels (kandus), pinnacles (thilas) and lagoons where powerful ocean currents sweep past colourful coral gardens. This nutrient‑rich flow attracts manta rays, whale sharks, reef sharks, schooling jacks, barracudas and every reef fish imaginable. Liveaboards and resort dive centres explore sites such as Okobe Thila and Kandooma Thila in the central atolls, manta cleaning stations in Baa and Ari, and shark‑filled channels like Fuvahmulah in the deep south. Diving here ranges from tranquil coral slopes to adrenalin‑fuelled drifts through current‑swept passes, making the Maldives a true pelagic playground.

Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef stretches for more than 2,300 km along Australia’s Queensland coast and is Earth’s largest coral ecosystem. With over 2,900 individual reefs, hundreds of islands, and a staggering diversity of marine life, it’s a bucket‑list destination for divers. Outer reef walls, coral gardens and pinnacles support potato cod, giant trevallies, reef sharks, sea turtles, manta rays and even visiting dwarf minke and humpback whales. Divers can explore historic wrecks like the SS Yongala, drift along the coral‑clad walls of Osprey Reef or mingle with friendly cod at Cod Hole. Whether you’re a beginner on a day trip from Cairns or an experienced diver on a remote liveaboard, the Great Barrier Reef offers unforgettable underwater adventures.

Manado

Tucked away in northern Sulawesi, Manado’s coastal waters and Bunaken National Park are a diver’s dream. Sheer coral walls plunge into the deep blue, exploding with sponges, sea fans and tropical fish, while the mainland coast hides muck‑diving gems with seahorses, ghost pipefish and mimic octopus. Dolphins and pilot whales sometimes cruise past, green turtles nap on the reef, and reef sharks and schooling jacks patrol the drop‑offs. Whether you like effortless drift dives along walls or critter hunting in sand and seagrass, Manado balances big‑fish thrills with macro treasures. Warm waters, friendly locals and laid‑back resorts make it perfect for both serious underwater photographers and casual holidaymakers.