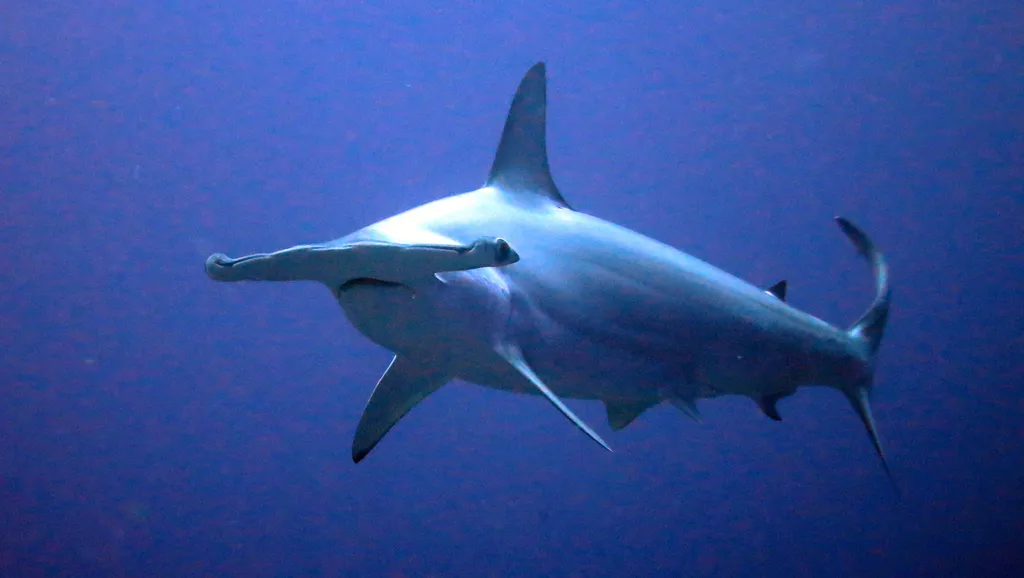

Hammerhead Shark

Sphyrnidae (family - 9 species)

Photo by Jake Mohan from Minneapolis / CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Few shark species inspire the same instant recognition as hammerheads - seeing that distinctive T-shaped head slicing through blue water is an unforgettable "only in nature" moment that reminds you evolution has no limits to creativity. But that bizarre hammer isn't just for show: it's a finely-tuned hunting instrument packed with hundreds of electroreceptors, providing 360-degree vision and the ability to detect stingrays buried under sand from meters away. Even more remarkably, these supposedly solitary apex predators gather in massive schools - sometimes hundreds or thousands strong - creating swirling walls of sharks that represent one of diving's most spectacular phenomena. For divers willing to venture to remote locations and brave strong currents, encountering a hammerhead school is a bucket-list experience that combines beauty, power, and a humbling reminder that in the ocean, you're just a visitor in their world.

🔬Classification

📏Physical Features

🌊Habitat Info

⚠️Safety & Conservation

Identification Guide

Photo by Rodtico21 (digital). / CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Hammer-Shaped Head (Cephalofoil): Distinctive T-shaped or shovel-shaped head

- Eyes on Wing Tips: Eyes positioned at far ends of head extensions

- Tall Dorsal Fin: Large, prominent first dorsal fin

- Size Varies by Species: From 90cm (bonnethead) to 6m+ (great hammerhead)

- Gray Coloration: Gray to brown dorsally, white belly

- Swimming Style: Elegant gliding with gentle head swaying

- Species Differences:

- Great: Very long, straight. wide hammer with central notch

- Scalloped: Rounded hammer with scalloped front edge, central indentation

- Smooth: Rounded hammer without central notch

- Bonnethead: Shovel-shaped, much narrower hammer

Top 10 Fun Facts about Hammerhead Shark

Photo by NOAA Photo Library via Wikimedia Commons

1. The Ultimate Multi-Tool: Cephalofoil Functions

That hammer-shaped head (technically called a cephalofoil) isn't evolutionary whimsy - it's a Swiss Army knife of adaptations. The wide placement of eyes provides near-360-degree vision in the vertical plane, allowing hammerheads to see above and below simultaneously - crucial for detecting both surface prey and bottom-dwelling targets while swimming. The flat surface creates lift like an airplane wing, improving maneuverability and allowing for tighter turns. Most impressively, the hammer serves as a weapon: great hammerheads literally use their heads as clubs to pin stingrays against the seafloor before biting, leaving hammer-shaped bruises on their prey. Some researchers even speculate the cephalofoil might act as a rudder or stabilizer during high-speed swimming.

2. The Super Sense: Enhanced Electroreception

All sharks have ampullae of Lorenzini - special pores that detect electrical fields from living creatures. But hammerheads have evolutionary advantage in spades. The broad surface area of the cephalofoil allows for hundreds more electroreceptors spread across a wider field, creating what's essentially an underwater metal detector on steroids. Research shows hammerheads can detect electrical signals as faint as one-billionth of a volt - sensitive enough to find a stingray's heartbeat through 30cm of sand. This explains why hammerheads swim with their heads swaying side to side like a metal detector sweep: they're literally scanning the seafloor for hidden prey's bioelectric signatures.

3. Shark Tornadoes: Massive Schooling Behavior

While most sharks are solitary, scalloped hammerheads form some of the ocean's largest shark aggregations - schools of 100-500+ individuals, sometimes reaching into the thousands. During daylight hours, these schools gather around seamounts and islands, creating swirling walls of sharks that rotate like living tornadoes. Scientists still debate why they school: theories include protection from larger predatory sharks (orcas, large great whites), social signaling for mating, improved navigation using magnetic fields, and energy-efficient swimming through slipstreaming. At night, the schools disperse and individuals hunt alone, then reconvene at dawn like office workers returning to a meeting.

4. The Hammerhead Triangle: Diving's Holy Grail

Three remote Pacific islands - Cocos Island (Costa Rica), Galapagos (Ecuador), and Malpelo (Colombia) - form what divers call the "Hammerhead Triangle," representing the most reliable places on Earth to encounter massive hammerhead schools. These volcanic seamounts rising from deep oceans create upwelling currents rich in nutrients, attracting prey species and consequently, hammerheads. Diving these sites requires liveaboard trips, strong current skills, and often deep dives (25-40m), but the reward is witnessing hundreds of hammerheads schooling overhead - an experience consistently rated among diving's Top 10 bucket list encounters.

5. Stingray Specialists: Built for the Hunt

While hammerheads eat diverse prey (fish, squid, octopus, crustaceans), they're specialized stingray hunters. The great hammerhead in particular has evolved specifically to hunt these venomous prey. They've developed some immunity to stingray venom - researchers have found great hammerheads with dozens of stingray barbs embedded in their mouths and heads, apparently unfazed. The hunting technique is brutal: using electroreceptors to locate buried rays, they pin them with the hammer, bite off the wings, then consume the body. One study found a great hammerhead with 96 stingray barbs in its mouth - a testament to either immunity or incredible pain tolerance.

6. Critically Endangered: Victim of the Fin Trade

Despite their iconic status, most hammerhead species are critically endangered or endangered. The great hammerhead is classified as Critically Endangered - one step from extinction. The primary threat? Shark finning for shark fin soup. Hammerhead fins are among the most valuable in the trade due to their large size and high fin ray counts. Their schooling behavior makes them tragically easy to catch in large numbers with purse seine and longline fishing. Some populations have declined by 80-90% in just 30 years. Conservation efforts now focus on protecting aggregation sites, banning fin trade, and creating marine protected areas.

7. Species Diversity: From Giants to Miniatures

The hammerhead family contains nine species ranging dramatically in size. The great hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran) grows to 6+ meters and 450+ kg - a true ocean giant and the largest hammerhead. The scalloped hammerhead (S. lewini) is the most commonly seen in schools, identifiable by its scalloped front edge and central head notch. The bonnethead (S. tiburo) is the family's miniature at just 0.9-1.5 meters, with a rounded, shovel-shaped head. Incredibly, bonnetheads are also the only known omnivorous shark - seagrass makes up a significant portion of their diet, which they can digest unlike other sharks.

8. Magnetic Navigation: Internal Compasses

Research on bonnetheads revealed that hammerheads possess magnetoreception - they can sense Earth's magnetic field and use it for navigation. In experiments, bonnetheads demonstrated clear directional preferences that changed when scientists altered the magnetic field. This explains how hammerheads navigate vast open oceans to return to specific seamounts year after year. The cephalofoil may play a role in this magnetic sensing, with some theories suggesting electromagnetic induction as the detection mechanism. Essentially, hammerheads have built-in GPS using Earth's magnetic highways.

9. Viviparous Birth: Large Litters

Hammerheads are viviparous, meaning they give live birth to fully-formed pups rather than laying eggs. Females have remarkably long gestation periods - 10-11 months in scalloped hammerheads, longer in great hammerheads. Litter sizes are impressive: scalloped hammerheads can birth 15-30 pups, while great hammerheads may have 6-42 pups per litter. Pups are born with soft hammers that harden as they grow, and they immediately disperse to shallow coastal nurseries where they spend their first years before venturing to deeper waters. Females only reproduce every 1-2 years, making population recovery slow.

10. Hammerhead Behavior: Shy Giants

Despite their impressive size and power, hammerheads are generally wary of divers. They typically maintain distance and often retreat when approached, making close encounters challenging. This shyness is partly why seeing large schools is so magical - you're witnessing behavior that doesn't involve human interaction. Great hammerheads in particular are notoriously camera-shy. The exception is when divers access cleaning stations or feeding grounds where hammerheads become habituated. Contrary to their fearsome appearance, attacks on humans are extraordinarily rare - only 17 recorded unprovoked attacks globally, with zero fatalities. They're far more threatened by us than we are by them.

Diving & Observation Notes

Photo by Barry Peters` / CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

🧭 Finding Hammerheads

Requires planning—these are pelagic wanderers, not reef residents.

- The Triangle: Cocos, Galapagos, and Malpelo are the holy trinity for massive schools.

- Go Deep & Blue: They patrol drop-offs and seamounts, often at 25-40m depth.

- Look Out: Don't just stare at the reef; constantly scan the open blue water.

🤿 Behavior & Observation

- Shy Giants: Unlike curious reef sharks, hammerheads are skittish. Chasing them guarantees they will flee.

- Schooling: If you see a wall of sharks, stay still. They may circle back if unthreatened.

- Scanning: Watch their heads sway side-to-side as they scan for electrical signals from prey.

📸 Photo Tips

- Wide Angle: Essential. You need to capture the scale of the school or the width of the head.

- Ambient Light: Strobes are useless for distant schools; rely on natural light and high ISO.

- Silhouette: Shoot upward to capture their iconic shape against the surface.

- Video: Often better than stills for capturing the movement of a school.

⚠️ Ethics & Safety

- Drift Diving: Encounters often happen in strong currents. Good buoyancy and drift skills are mandatory.

- No Chasing: It stresses the animals and ruins the encounter for everyone.

- Respect: These are apex predators. Maintain a respectful distance.

🌏 Best Locations

- Cocos Island (Costa Rica): The gold standard for schooling hammerheads.

- Galapagos (Ecuador): Darwin and Wolf islands are legendary.

- Banda Sea (Indonesia): Seasonal schooling (Oct-Nov) in the Ring of Fire.

- Red Sea (Egypt): Daedalus and Elphinstone for solitary or small groups.

- Yonaguni (Japan): Winter schooling season.

Best Places to Dive with Hammerhead Shark

Cocos Island

Cocos Island sits 550 km off Costa Rica’s Pacific coast and is only accessible by liveaboard. This uninhabited, jungle‑clad island was described by Jacques Cousteau as “the most beautiful island in the world.” Divers come here for the pelagic action: schooling scalloped hammerheads patrol the reef points and pinnacles, tiger sharks and Galápagos sharks cruise the blue, and manta rays and whale sharks glide past during the wet season. Visibility and sea conditions vary with the seasons, but the island’s underwater topography of walls, cleaning stations and steep pinnacles makes every dive an adventure. Currents can be strong and depths often exceed 30 m, so Cocos is considered an advanced destination. Trips are normally 9–10 days with a 36‑hour crossing each way from the mainland, and most operators include guided island hikes between dives.

Galapagos

The Galápagos Islands sit 1 000 km off mainland Ecuador and are famous for their remarkable biodiversity both above and below the water. Created by volcanic hot spots and washed by the converging Humboldt, Panama and Cromwell currents, these remote islands offer some of the most exhilarating diving on the planet. Liveaboard trips venture north to Darwin and Wolf islands, where swirling schools of scalloped hammerheads and hundreds of silky and Galápagos sharks patrol the drop‑offs. Other sites host oceanic manta rays, whale sharks, dolphins, marine iguanas, penguins and playful sea lions. Strong currents, cool upwellings and surge mean the dives are challenging but incredibly rewarding. On land you can explore lava fields, giant tortoise sanctuaries and blue‑footed booby colonies.

Banda Sea

Hidden between Indonesia’s Maluku Islands lies the Banda Sea – an untouched stretch of ocean famous for its schools of hammerhead sharks and abundant sea snakes. Part of the Coral Triangle, this remote sea spans over half a million square kilometres and plunges to depths beyond 7 km. Cold, nutrient‑rich upwellings feed pristine reefs bursting with life: imagine gliding along steep walls encrusted with giant gorgonians while dogtooth tuna, thresher sharks and squadrons of mobula rays cruise past. Volcanic islands such as Manuk and Gunung Api rise from the blue, their warm vents attracting banded sea kraits by the dozen and drawing divers from all over the world. Because there are no large towns here, the Banda Sea is usually explored on liveaboards – the reward is some of Indonesia’s wildest and most exhilarating diving.

Hurghada (Red Sea)

Hurghada is one of Egypt’s original Red Sea resorts and remains a popular base for day‑boat diving and liveaboard departures. Situated on the mainland’s eastern shore, the city offers easy access to a wide variety of reefs, wrecks and islands within a short boat ride. Warm, clear waters, gentle conditions and lively coral gardens make Hurghada ideal for training and fun diving, while nearby sites such as Abu Nuhas and the Thistlegorm wreck keep more experienced divers enthralled. Topside, the modern resort town boasts a lively promenade, international restaurants and plenty of après‑dive entertainment.

Maldives

Scattered across the Indian Ocean like strings of pearls, the Maldives’ 26 atolls encompass more than a thousand low‑lying islands, reefs and sandbanks. Beneath the turquoise surface are channels (kandus), pinnacles (thilas) and lagoons where powerful ocean currents sweep past colourful coral gardens. This nutrient‑rich flow attracts manta rays, whale sharks, reef sharks, schooling jacks, barracudas and every reef fish imaginable. Liveaboards and resort dive centres explore sites such as Okobe Thila and Kandooma Thila in the central atolls, manta cleaning stations in Baa and Ari, and shark‑filled channels like Fuvahmulah in the deep south. Diving here ranges from tranquil coral slopes to adrenalin‑fuelled drifts through current‑swept passes, making the Maldives a true pelagic playground.

Fiji

Fiji sits like a necklace of more than 300 inhabited islands and 500 smaller islets in the heart of the South Pacific. Jacques Cousteau dubbed it the “soft coral capital of the world” for good reason – nutrient‑rich currents wash over sloping reefs, walls and bommies that erupt in shades of pink, purple, orange and yellow. The country’s dive sites range from kaleidoscopic coral gardens and pinnacles in the Somosomo Strait to shark dives in Beqa Lagoon, and remote passages in Bligh Water and the Koro Sea. Schools of barracuda, trevally and surgeonfish cruise above while manta rays, turtles, bull sharks and occasionally hammerheads glide past. Friendly locals and a relaxed island vibe make Fiji a favourite for both adventurous liveaboard trips and leisurely resort‑based diving.