Hydroid

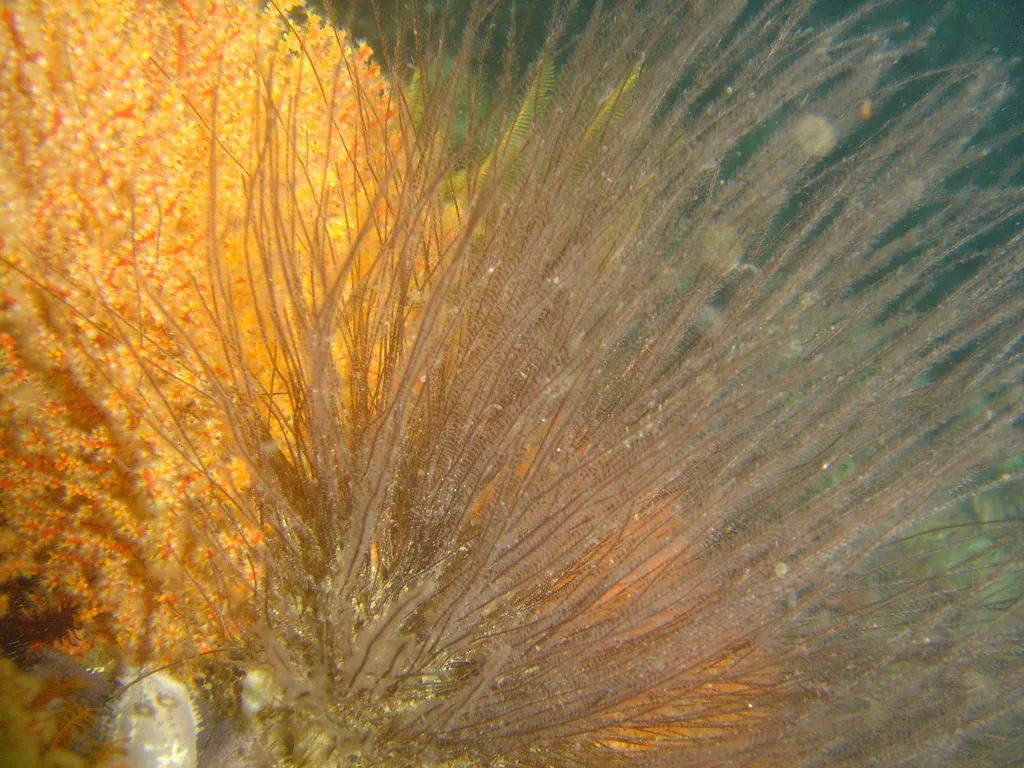

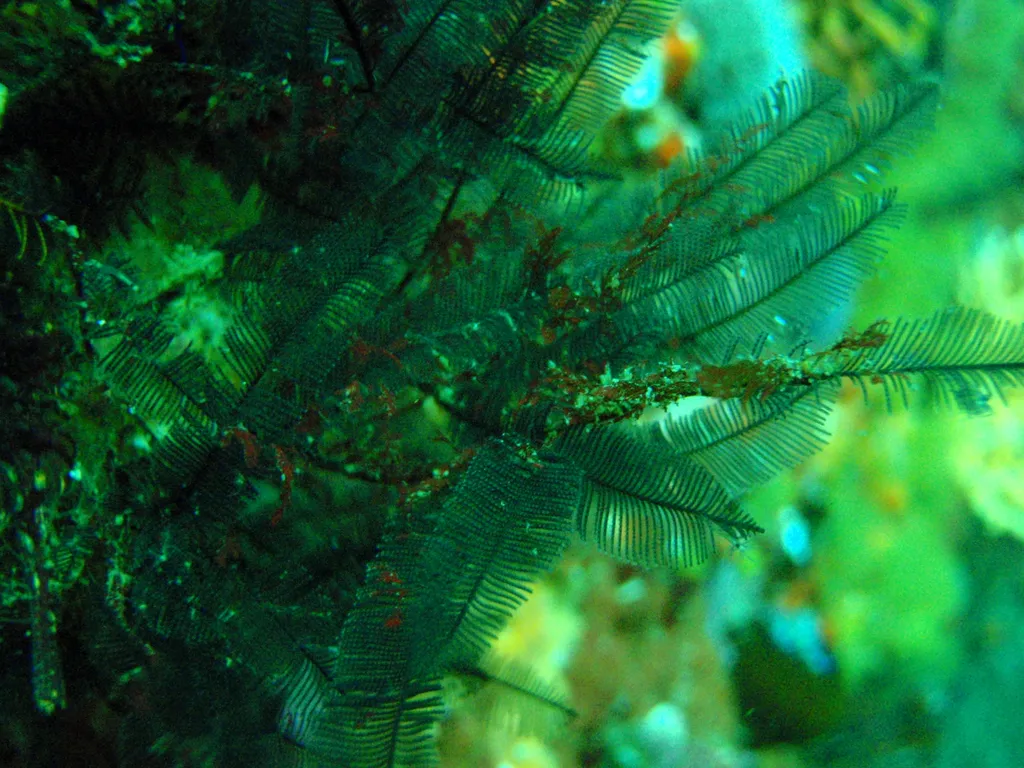

Hydrozoa (hydroid stage)

Photo by Jerry Kirkhart from Los Osos / CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

To most divers, hydroids are those fuzzy, plant-like growths coating rocks, ropes, and sea fans—easy to overlook until you brush against them and feel an unexpected sting. But look closely, and you'll discover that each "fuzz" patch is actually a colony of tiny predators, hundreds or thousands of polyps armed with stinging cells. Hydroids are the polyp stage of hydrozoans, relatives of jellyfish and fire corals, and they come in an astonishing variety of forms: delicate feather-like plumes, fine hair-like films, bushy tufts, or intricate trees growing on gorgonians, algae, and even other animals. Each polyp is a tiny hunter, extending its tentacles into the current to snare passing plankton with microscopic harpoons. For macro-obsessed divers, hydroids are a treasure map—pygmy seahorses, pipefish, shrimp, and nudibranchs all use hydroid forests as hunting grounds, camouflage, or nurseries. But they're also the hidden cause of many "mystery rashes" after dives: that innocent-looking fuzz on the mooring line may be a dense carpet of stinging hydroids.

🔬Classification

📏Physical Features

🌊Habitat Info

⚠️Safety & Conservation

Identification Guide

Photo by User: (WT-shared) Seascapeza at wts wikivoyage / CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Plant-Like Fuzz: Hydroids often look like tiny ferns, moss, or algae rather than animals

- Branching Colonies: Colonies form fine, repeatedly branching stems with rows or whorls of tiny polyps

- Polyps: Each polyp has a cylindrical body and a ring or crown of tentacles, usually only a few millimeters long

- Substrate Choice: Common on gorgonians, black corals, algae, seagrass blades, rock overhangs, ropes, mooring lines, and wrecks

- Color: Translucent white, pale yellow or brown; sometimes orange, pink, or with contrasting tips

- Medusa Buds: Some species produce small medusa buds or capsules that look like tiny spheres on branches

- Not Soft Coral: Unlike soft corals, hydroids lack obvious eight-fold symmetry and often have much finer, hair-like structure

- Sting Clue: Areas that look like harmless fuzz but cause a mild sting on contact are often hydroids

Top 10 Fun Facts about Hydroid

Photo by Peter Southwood / CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

1. The Hidden Forests of the Reef

Hydroids form some of the most extensive "micro-forests" on reefs, docks, and wrecks, but most divers never realize they're looking at animals. Colonies can carpet entire boulders, mooring lines, or gorgonians in a fine fuzz that's easy to mistake for algae. Each colony starts from a single polyp that buds repeatedly, sending out stolons (creeping stems) and upright branches that support feeding polyps. Over time, a single founder can create a three-dimensional forest of stinging tentacles that becomes prime real estate for a whole community of small creatures. For divers, recognizing hydroid forests turns previously "boring" areas of fuzz into high-interest macro terrain packed with life.

2. Two Lives in One: Polyp and Medusa

Many hydroids have one of the most complex life cycles among cnidarians, alternating between a sessile polyp colony and a free-swimming medusa. The hydroid phase you see on rocks and sea fans is only half the story: some species bud off tiny medusae—miniature jellyfish—that drift into the plankton, feeding and eventually producing gametes. After fertilization, the resulting planula larvae settle and grow into new hydroid colonies. In other species, the medusa stage is reduced or completely suppressed, with reproductive structures remaining attached to the colony. For divers, this means that the hydroid fuzz you photograph today might be releasing microscopic jellyfish into the water column tomorrow—an invisible connection between benthic and pelagic worlds.

3. Stinging Fuzz: Micro-Harpoons in Action

Hydroid polyps are armed with nematocysts—the same stinging cells used by jellyfish and fire corals. Each tentacle is lined with microscopic harpoons that can fire on contact, injecting venom into tiny prey or unlucky fingers. For plankton-sized victims, a single sting can be fatal. For divers, hydroid stings usually cause only mild to moderate irritation—itchy red patches or a rash that may appear minutes to hours after contact. However, repeated exposure or sensitive skin can lead to more intense reactions. Many divers blame "mystery rashes" on wetsuits or jellyfish when the real culprits are hydroid-coated mooring lines, anchor ropes, or coral rubble. Understanding this helps you connect that strange itch on your wrist with the fuzzy rope you grabbed while doing a safety stop.

4. Chemical Warfare: Beyond Stinging Cells

While nematocysts are the first line of defense, many hydroids also wage chemical warfare. They produce secondary metabolites—complex organic compounds that deter predators, inhibit the growth of competitors, or prevent fouling organisms from settling on their colonies. Some of these compounds are potent enough to discourage fish, nudibranchs, or other invertebrates from grazing on the hydroids. Others seem to mediate competition for space on crowded reefs, allowing hydroids to hold their ground against sponges, algae, and even corals. For scientists, hydroids are a promising source of new bioactive compounds with potential pharmaceutical applications. For divers, this means that hydroid forests aren't just visually interesting—they're chemically sophisticated battlegrounds where invisible wars are being fought at the microscopic level.

5. The Hermit Crab's Hairdo: Snail Fur Hydroids

One of the most charming hydroid stories involves hermit crabs and a hydroid called Hydractinia echinata. This species often colonizes gastropod shells occupied by hermit crabs, creating a fuzzy coat known as "snail fur." The relationship is fascinating: the hydroid gains mobility and access to food-rich currents as the hermit crab moves around, while the hermit crab gains a living defense system—predators that try to grab the shell get a face full of stinging tentacles. Some studies suggest this relationship may even influence hermit crab shell choice, with crabs preferring shells already colonized by hydroids. For divers, spotting a hermit crab with a fuzzy, living coat is a highlight of any macro dive, and recognizing that the "fur" is a hydroid colony adds another layer of appreciation.

6. Fouling Masters: From Dock Lines to Ship Hulls

Hydroids are classic fouling organisms, meaning they readily colonize artificial structures like docks, piers, buoys, aquaculture nets, and ship hulls. Their ability to grow quickly, reproduce asexually, and tolerate a range of conditions makes them ideal colonizers of man-made surfaces. For the shipping and aquaculture industries, this fouling can be a major problem: hydroid growth increases drag on ships, clogs nets, and provides surfaces for yet more fouling organisms to attach. Some hydroids can even damage fish in aquaculture by stinging exposed tissues. For divers, this fouling behavior means that the best places to see dense hydroid growth are often not pristine reefs, but humble structures like pier pilings, mooring lines, and fish farm cages—spots that casual divers often ignore.

7. Shape-Shifters: Morphological Plasticity

Hydroid colonies are masters of morphological plasticity—they can change their growth form depending on environmental conditions. In strong currents, colonies may grow shorter and more compact, reducing drag. In calm water, they may develop taller, more delicate branches to maximize feeding area. Light levels, substrate type, and competition from neighbors can all influence colony architecture. This plasticity makes hydroids highly adaptable and helps explain why they're found in such a wide range of habitats, from shallow surge zones to deep, quiet basins. For divers, this means that hydroids on a high-energy reef crest might look completely different from those on a sheltered dock piling, even if they're the same species. Recognizing this shape-shifting ability helps you avoid assuming that different-looking colonies must be different animals.

8. Micro-Habitats: Nurseries for Macro Life

Despite their tiny size, hydroid colonies create critical micro-habitats that support a surprising amount of macro life. Small shrimp, crabs, juvenile fish, and especially nudibranchs all use hydroid forests for shelter, hunting, and camouflage. Many nudibranch species specialize in feeding on specific hydroids, often stealing their nematocysts and reusing them for their own defense. Pygmy seahorses and pipefish sometimes associate with hydroid-covered gorgonians, using the fine branches as camouflage. For divers, this means that whenever you find hydroids, you should slow down and look very carefully—what initially looks like a simple fuzz patch may hide multiple cryptic species. Hydroids turn otherwise bare rock or rope into a three-dimensional apartment complex for invertebrates and small fishes, dramatically increasing local biodiversity.

9. Freshwater Cousins: Hydra in the Pond

While most hydroids are marine, one famous group lives in freshwater: the genus Hydra. These solitary hydroids lack a medusa stage entirely and spend their whole lives as individual polyps attached to plants, rocks, or debris in ponds and streams. Hydra are famous in biology for their extraordinary regenerative abilities—cut them into pieces, and each piece can regrow into a complete animal. Some studies suggest that Hydra may be effectively "immortal" under laboratory conditions, with no clear signs of aging. Although divers rarely encounter Hydra underwater (they're too small and live in freshwater), knowing about them expands our view of hydroids beyond the ocean. It also highlights the incredible diversity within Hydrozoa, from marine fouling colonies to immortal freshwater polyps used in cutting-edge aging research.

10. The Diver's Itch: Recognizing and Avoiding Hydroids

For divers, hydroids are both fascinating and mildly hazardous. Contact with hydroid colonies can cause red, itchy welts or rashes known informally as "hydroid dermatitis" or "seabather's rash" (though the latter is more commonly linked to jellyfish larvae). The reaction may be immediate or delayed, and repeated exposure can make reactions worse over time. Common culprits include hydroids growing on downlines, mooring ropes, and shallow reef rubble where divers rest their hands or knees. The good news is that these stings are usually mild and self-limiting, resolving in a few days. Protective measures are simple: wear a full suit or rash guard, avoid grabbing fuzzy ropes or rocks, and practice good buoyancy so you don't accidentally brush against hydroid-covered surfaces. Understanding hydroids turns an annoying rash into a teachable moment—and a reminder to look more closely at the "fuzz" next time.

Diving & Observation Notes

Photo by Peter Southwood / CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

🧭 Finding Hydroids

- Where to Look: Check gorgonians, black corals, soft corals, algae, seagrass edges, ropes, mooring lines, pier pilings, and wreck railings.

- Depth: Common from a few meters to 40m+; also present on deeper walls but harder to inspect.

- Lighting: Often easier to see with a torch—backlighting reveals the fine, feathery branches.

- Hotspots: Areas with moderate current and plenty of hard surfaces are usually rich in hydroids.

🤿 Behavior & Observation

- Feeding Times: Polyps tend to extend tentacles more when plankton is abundant—often at dusk, night, or during strong tidal flows.

- Retraction: Many hydroids retract polyps quickly when disturbed—wait a minute or two and they often re-extend.

- Associates: Look for nudibranchs, shrimps, crabs, pipefish, and juvenile fish living among the branches.

- Life Cycle: Remember that some of the jellyfish you see in the plankton may be the medusa stage of hydroids growing on the reef below.

📸 Photo Tips

- Macro is King: A good macro or close-up lens is essential—individual polyps and tentacles are tiny.

- Dark Backgrounds: Position yourself to get dark water or shaded rock behind the colony to make the hydroid stand out.

- Side Lighting: Use strobes or video lights from the side to bring out texture and translucence.

- Subject Isolation: Use shallow depth of field to separate hydroids from messy backgrounds.

- Story Shots: Include associated critters (nudibranchs, hermit crabs, pipefish) to tell the full ecological story.

⚠️ Safety & Ethics

- Skin Protection: Wear a full suit or rash guard and gloves when working near hydroid-covered ropes or rocks.

- Hands Off: Avoid touching hydroids or resting on fuzzy surfaces—both to protect your skin and the colonies.

- Buoyancy: Good trim and buoyancy prevent accidental contact with hydroid forests on slopes and walls.

- No Collection: Do not scrape or collect hydroids—they're important habitat builders.

- Awareness: If you develop a rash after a dive, consider whether you handled hydroid-covered lines or rocks.

🌏 Best Locations

- Lembeh & Anilao: Critter capitals with hydroids everywhere on ropes, rubble, and gorgonians.

- Tulamben & Dumaguete: Lava slopes and rubble fields with hydroids hosting nudibranchs and shrimp.

- Pacific Northwest (BC/Washington): Kelp forests and rocky walls covered in cold-water hydroid species.

- Mediterranean & Atlantic Piers: Dock pilings and harbor walls rich in fouling hydroids.

- Any Pier or Jetty: Globally, pier structures are hydroid magnets—perfect for macro hunting.

Best Places to Dive with Hydroid

Lembeh

The Lembeh Strait in North Sulawesi has become famous as the muck‑diving capital of the world. At first glance its gently sloping seabed of black volcanic sand, rubble and discarded debris looks bleak. Look closer and it is teeming with weird and wonderful life: hairy and painted frogfish, flamboyant cuttlefish, mimic and blue‑ringed octopuses, ornate ghost pipefish, tiny seahorses, shrimp, crabs and a rainbow of nudibranchs. Most dives are shallow and calm with little current, making it an ideal playground for macro photographers. There are a few colourful reefs for a change of scenery, but Lembeh is all about searching the sand for critter treasures.

Anilao

Anilao, a small barangay in Batangas province just two hours south of Manila, is often called the macro capital of the Philippines. More than 50 dive sites fringe the coast and nearby islands, offering an intoxicating mix of coral‑covered pinnacles, muck slopes and blackwater encounters. Critter enthusiasts come for the legendary muck dives at Secret Bay and Anilao Pier, where mimic octopuses, blue‑ringed octopuses, wonderpus, seahorses, ghost pipefish, frogfish and dozens of nudibranch species lurk in the silt. Shallow reefs like Twin Rocks and Cathedral are covered in soft corals and teem with reef fish, while deeper sites such as Ligpo Island feature gorgonian‑covered walls and occasional drift. Because Anilao is so close to Manila and open year‑round, it’s the easiest place in the Philippines to squeeze in a quick diving getaway.

Tulamben(Bali)

Tulamben sits on Bali’s northeast coast and is best known for the USAT Liberty shipwreck – a 125‑metre cargo ship torpedoed in WWII that now lies just a short swim from shore. Warm water, mild currents and straightforward shore entries make diving here relaxed for all levels. Besides the wreck, divers can explore coral gardens, black‑sand muck sites and dramatic drop‑offs. Macro lovers will find nudibranchs, ghost pipefish, mimic octopus and pygmy seahorses, while big‑fish fans can encounter schooling jackfish, bumphead parrotfish and reef sharks. With a compact coastline packed with variety, Tulamben delivers world‑class wreck and critter diving without long boat rides.

Dumaguete

Dumaguete on the southeast coast of Negros is the jumping‑off point for some of the Philippines’ most diverse diving. Along the nearby town of Dauin, a series of shallow marine sanctuaries and black‑sand slopes hide critters galore: frogfish, flamboyant cuttlefish, mimic octopus, ghost pipefish, seahorses, pipefish and nudibranchs. Artificial reefs made from car tyres and pyramids provide extra habitat. Offshore, Apo Island’s walls and plateaus burst with hard and soft corals, schooling jacks and barracudas, and friendly green turtles. With day trips to Oslob’s whale sharks or Bais’ dolphin‑watching, and excursions to nearby Siquijor, Dumaguete offers a perfect mix of macro muck diving and classic coral reefs.

Raja Ampat

Raja Ampat, the “Four Kings,” is an archipelago of more than 1,500 islands at the edge of Indonesian West Papua. Its reefs sit in the heart of the Coral Triangle, where Pacific currents funnel nutrients into shallow seas and feed the world’s richest marine biodiversity. Diving here means gliding over colourful walls and coral gardens buzzing with more than 550 species of hard and soft corals and an estimated 1,500 fish species. You’ll meet blacktip and whitetip reef sharks on almost every dive, witness giant trevally and dogtooth tuna hunting schools of fusiliers, and encounter wobbegong “carpet” sharks, turtles, manta rays and dolphins. From cape pinnacles swarming with life to calm bays rich in macro critters, Raja Ampat offers endless variety. Above water, karst limestone islands and emerald lagoons provide spectacular scenery between dives.