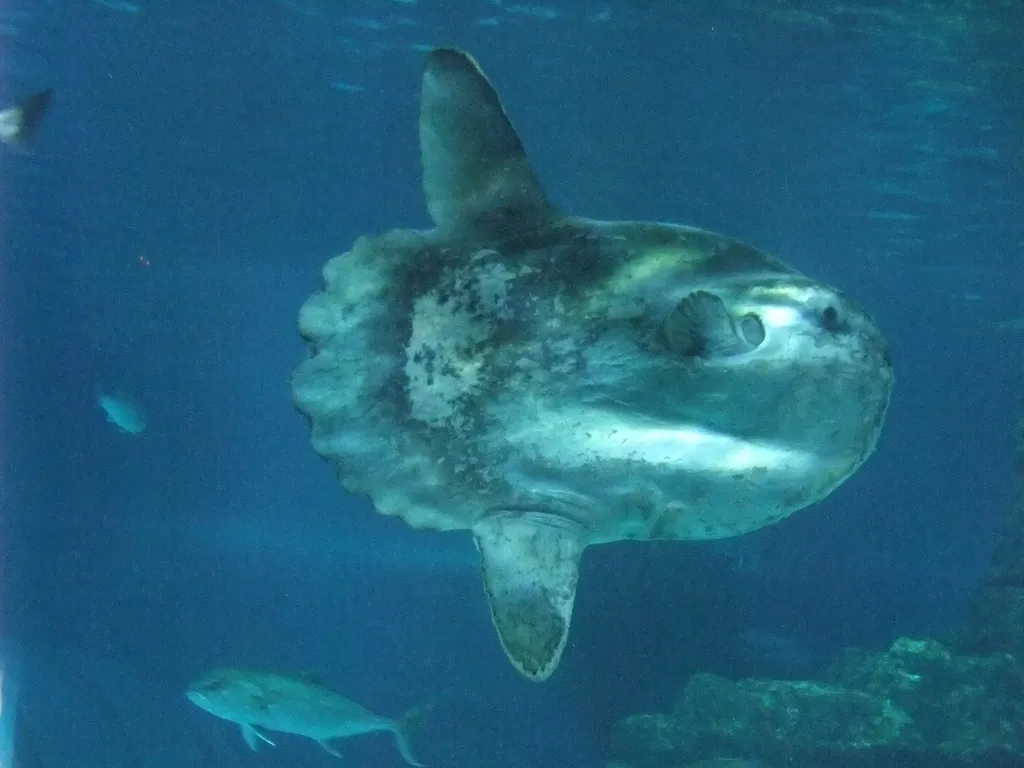

Mola mola

Mola mola

Photo by Nol Aders / CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The Mola mola, or Ocean Sunfish, is the heaviest bony fish in the world and arguably the weirdest. Looking like a giant floating head that lost its body, it can weigh more than a car and grow up to 3 meters tall. Despite their massive size, they feed almost exclusively on jellyfish, slurping them up like spaghetti. They are famous for "basking" sideways on the surface to warm up after deep, cold dives. Gentle, goofy, and infested with parasites, they are the holy grail for many divers, especially in places like Bali.

🔬Classification

📏Physical Features

🌊Habitat Info

⚠️Safety & Conservation

Identification Guide

Photo by U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration via Wikimedia Commons

Field marks:

- Shape: A giant, flat, disc-like body that looks truncated (cut off) at the back.

- Fins: Two massive fins (dorsal and anal) that wave in unison like vertical oars; no tail fin (caudal fin), instead a rudder-like "clavus".

- Mouth: Small, permanently open mouth with fused teeth (beak-like).

- Movement: Sculls slowly through the water; often seen drifting sideways at the surface.

- Size: Absolutely massive. You won't mistake it for anything else.

Juvenile vs. Adult

Larval Molas look like tiny spiky pufferfish (less than 5mm). They lose the spikes and grow a "tail" as they mature. The growth from larva to adult is an increase in mass of over 60 million times!

Top 10 Fun Facts about Mola mola

Photo by Javi Guerra Hernando / CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

1. The Fish That Lost Its Tail: Evolution's Strangest Edit

When you first see a Mola mola, your brain struggles to process what it's looking at. It genuinely appears to be the front half of a fish—as if someone took a giant cleaver and lopped off everything behind the dorsal fin. But this isn't an injury; it's millions of years of evolution at work. The scientific name Mola comes from the Latin word for "millstone", describing its round, grey, rough-textured body. Germans call it Schwimmender Kopf, which translates to "swimming head"—a name that's surprisingly anatomically accurate. What happened to the tail? The Mola's ancestors had normal fish tails, but over evolutionary time, the caudal vertebrae compressed and fused into a structure called the clavus—a stiff, rudder-like pseudo-tail that looks like someone ironed a frilly curtain onto the back of a dinner plate. It's one of the most radical body plans in the entire fish kingdom, and it works just fine.

2. Solar-Powered Giants: The Science of Sunbathing

The English name "Ocean Sunfish" isn't just poetic—it describes a crucial survival behavior. Molas are heterothermic, meaning their body temperature fluctuates with their environment. When hunting, they dive to depths exceeding 600 meters where water temperatures can drop to near-freezing. These hunting expeditions target deep-sea delicacies: squid, siphonophores, and gelatinous zooplankton that drift in the twilight zone. But there's a problem: cold muscles don't digest food well. So after a deep dive, the Mola returns to the surface and rolls onto its side, presenting its massive flank to the sun like a solar panel. Scientists call this "thermal recharging"—the fish is literally using sunlight to warm its core, speed up digestion, and prepare for the next plunge into the abyss. Some researchers have tracked individual Molas making multiple vertical migrations per day, descending to hunt, ascending to warm up, in an endless cycle of yo-yo diving.

3. The Most Prolific Mother in the Vertebrate Kingdom

If there were an award for "Most Eggs Produced by a Backboned Animal," the Mola mola would win by a landslide. A single female can carry up to 300 million eggs at one time—that's more than any other known vertebrate on Earth. To put this in perspective, a human woman releases about 400 eggs in her lifetime; a female Mola releases nearly a million times that number in a single spawning event. Why such astronomical fecundity? It's a numbers game against impossible odds. Mola larvae are among the most vulnerable creatures in the ocean: tiny, spiky, and utterly defenseless. The survival rate is estimated at roughly one in a million. Of those 300 million eggs, perhaps a few hundred might survive to adulthood. Evolution's answer to this brutal attrition? Produce so many offspring that even catastrophic losses can't wipe out the lineage. It's reproduction through sheer statistical force.

4. The Greatest Growth Spurt in Nature

When a Mola mola hatches, it's a 2.5-millimeter speck—smaller than a grain of rice—covered in spines that make it look like a microscopic sea urchin crossed with a cartoon pufferfish. Fast forward a few years, and that same animal can weigh over 2,000 kilograms and stand taller than a basketball hoop. This represents a mass increase of approximately 60 million times the original body weight. To visualize this: imagine a human baby growing not to adult size, but to the mass of six Titanic ocean liners. No other vertebrate even comes close to this rate of growth. The transformation is so extreme that for years, scientists thought larval Molas were a completely different species. Those defensive spines? They gradually absorb into the body as the fish grows, leaving behind the smooth, leathery hide of the adult.

5. The Jellyfish Vacuum: Surviving on Nature's Empty Calories

Here's a metabolic puzzle: how does a fish grow to the size of a small car while eating food that's 95% water? The answer is volume, volume, volume. Molas feed primarily on jellyfish, salps, ctenophores, and other gelatinous zooplankton—creatures so nutritionally sparse that eating one is like consuming a bag of water with a few vitamins dissolved in it. A Mola must consume absolutely staggering quantities of these gelatinous blobs to sustain its bulk. Studies have shown individual sunfish eating hundreds of pounds of jellyfish per day. Their digestive system is essentially a continuous processing plant, extracting every possible calorie from an endless conveyor belt of marine gelatin. This diet also explains their slow lifestyle—when your food is mostly water, you can't afford to burn calories on unnecessary movement.

6. The World's Most Infested Fish

Being a giant, slow-moving, flat creature in the open ocean makes you an irresistible target for parasites. And Molas are absolutely riddled with them. Scientists have documented up to 40 different species of parasites living on a single individual, including copepods, isopods, flatworms, and various larvae. Some parasites burrow into the skin. Some attach to the gills. Some—disturbingly—live inside the eyeballs. This parasite load is so severe that Molas have developed an entire behavioral repertoire dedicated to getting clean. They visit "cleaning stations" on reefs where smaller fish pick parasites off their skin. They breach out of the water, hoping the impact will dislodge hitchhikers. They even recruit seabirds for help. A Mola's life is essentially an ongoing battle against being eaten alive from the outside in.

7. Breach for Relief: The World's Most Desperate Belly Flop

Given their lethargic reputation, it's shocking to learn that Molas can launch their entire body out of the water. We're talking about a fish that weighs as much as a car, exploding through the surface and crashing back down in a thunderous belly flop. Why would a creature so seemingly designed for slow, gentle movement perform such an energetically costly stunt? The leading theory involves—you guessed it—parasites. Scientists believe the impact of landing helps dislodge stubborn parasites that resist other removal methods. It's the aquatic equivalent of a dog shaking off water, except the dog weighs a ton and the "water" is hundreds of tiny creatures trying to eat it. Some researchers have observed Molas breaching multiple times in succession, apparently determined to shake off every last hitchhiker. It's desperation in slow motion.

8. The Bird Spa: An Unlikely Symbiosis

When fish cleaners aren't cutting it, Molas get creative. They rise to the surface, roll onto their side, and extend a fin above the waterline—essentially waving a flag that says "FREE FOOD HERE." This signal attracts seabirds, particularly gulls and albatrosses, who land directly on the floating fish and begin pecking parasites off its exposed skin. It's one of the rarest forms of symbiosis in nature: a fish actively recruiting birds for medical treatment. The birds get an easy meal; the Mola gets relief from its parasitic burden. Scientists have photographed Molas floating motionless while multiple birds stand on their flanks, methodically working over the skin like dermatologists at a very unusual clinic. In a world where fish and birds are usually predator and prey, this collaboration is remarkably peaceful.

9. Faster Than They Look: The Secret Athlete

For decades, scientists assumed Molas were essentially living driftwood—passive creatures pushed around by currents, too awkward to swim with any purpose. Then came satellite tracking, and the Mola's reputation got a complete overhaul. Tagged individuals have been recorded traveling 26 kilometers per day and diving to depths exceeding 600 meters. Some have crossed entire ocean basins. Far from being helpless drifters, Molas are deliberate, long-distance migrants capable of navigating thousands of kilometers through the open sea. They just don't look the part. Their unusual body shape—tall, flat, with vertically oriented fins—is actually highly efficient for the way they swim: sculling through the water with synchronized sweeps of their dorsal and anal fins, like a creature rowing with two oars. The lazy appearance is an illusion; underneath that goofy exterior is a surprisingly capable traveler.

10. The "Toppled Car Fish": Superstition and Naming

In Chinese, the Mola mola is called 翻车鱼 (Fān Chē Yú), which translates to "Toppled Car Fish" or "Overturned Vehicle Fish." The name comes from its distinctive surface behavior: when a Mola baskes at the surface, lying on its side with one fin pointing skyward, it looks remarkably like a wheel that's fallen off a cart. But this name carries baggage. In Chinese culture, the phrase "翻车" (toppled car) is associated with bad luck, accidents, and failure. Fishermen in some regions traditionally considered it unlucky to catch a Mola—hauling one aboard was seen as an omen of capsizing or disaster. Some would release the fish immediately, wanting no part of the jinxed creature. It's a fascinating case of how naming can shape human behavior toward a species. The Mola, of course, has no idea it's become a swimming superstition—it just keeps floating, oblivious to its reputation as a herald of misfortune.

Diving & Observation Notes

Photo by Sonse / CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

🧭 Finding Mola Mola

Bali (Nusa Penida) is the world capital for Mola sightings (July–Oct). Look for them at deep cleaning stations (Crystal Bay, Blue Corner). They hang vertically or at an angle, motionless, while bannerfish clean them. Look for the silhouette of a giant plate fading into the deep blue.

🤿 Approach & Behavior

- Be Invisible: They are extremely shy and easily startled by bubbles. Approach slowly and do not swim directly at them.

- Wait Your Turn: If a Mola is at a cleaning station, stay back (10m+). If you rush in, it will leave, ruining the show for everyone.

- No Chasing: You cannot outswim a Mola. If it turns away, let it go. Chasing stresses them.

- Bubble Control: Try to breathe gently. Loud, explosive bubbles scare them off.

📸 Photo Tips

- Wide Angle: You need a wide lens. They are huge.

- Silhouette: Shooting up from below against the sun creates a dramatic silhouette of their alien shape.

- Diver for Scale: Include a diver in the frame; otherwise, it just looks like a weird cookie. You need the reference to show it’s the size of a door.

⚠️ Ethics & Safety

- Do Not Touch: They have a protective mucus layer. Touching removes it and leads to infection.

- Deep Dives: Mola dives are often deep (30m+) with strong, cold currents (thermoclines). Watch your NDL and air.

- Flash: Avoid blasting them with strobes if they are shy; it can spook them.

🌏 Local Guide Nuggets

- Nusa Penida (Bali): "Crystal Bay" is the classic spot, but it’s crowded. "Blue Corner" has more currents but often bigger/more Molas.

- Galapagos: Often seen at Punta Vicente Roca, cleaning in the cold upwellings.

- Alor (Indonesia): Sometimes seen surfacing in the channel currents.

Best Places to Dive with Mola mola

Lembongan

Nusa Lembongan and its neighbouring islands sit on the edge of the Lombok Strait, where strong currents carry nutrient‑rich water between the Pacific and Indian oceans. This constant water flow produces clear visibility and supports vibrant reefs full of reef fish, trevallies and reef sharks. The area is famous for exhilarating drift dives; experienced divers drop into channels and ride the current over coral walls and slopes. Pelagic highlights include year‑round manta rays at nearby Manta Point and Manta Bay, while the rare ocean sunfish (Mola alexandrini) visits from July–October when cold upwellings bring temperatures as low as 16 °C. Beginner divers aren’t forgotten—sheltered sites like Lembongan Bay and Mangrove offer calm conditions, sandy bottoms and colourful coral gardens. With easy access by fast boat from Bali, Lembongan provides a perfect base to explore the more than two dozen sites around the Nusa islands.

Galapagos

The Galápagos Islands sit 1 000 km off mainland Ecuador and are famous for their remarkable biodiversity both above and below the water. Created by volcanic hot spots and washed by the converging Humboldt, Panama and Cromwell currents, these remote islands offer some of the most exhilarating diving on the planet. Liveaboard trips venture north to Darwin and Wolf islands, where swirling schools of scalloped hammerheads and hundreds of silky and Galápagos sharks patrol the drop‑offs. Other sites host oceanic manta rays, whale sharks, dolphins, marine iguanas, penguins and playful sea lions. Strong currents, cool upwellings and surge mean the dives are challenging but incredibly rewarding. On land you can explore lava fields, giant tortoise sanctuaries and blue‑footed booby colonies.