Seagrass

Alismatales (multiple families)

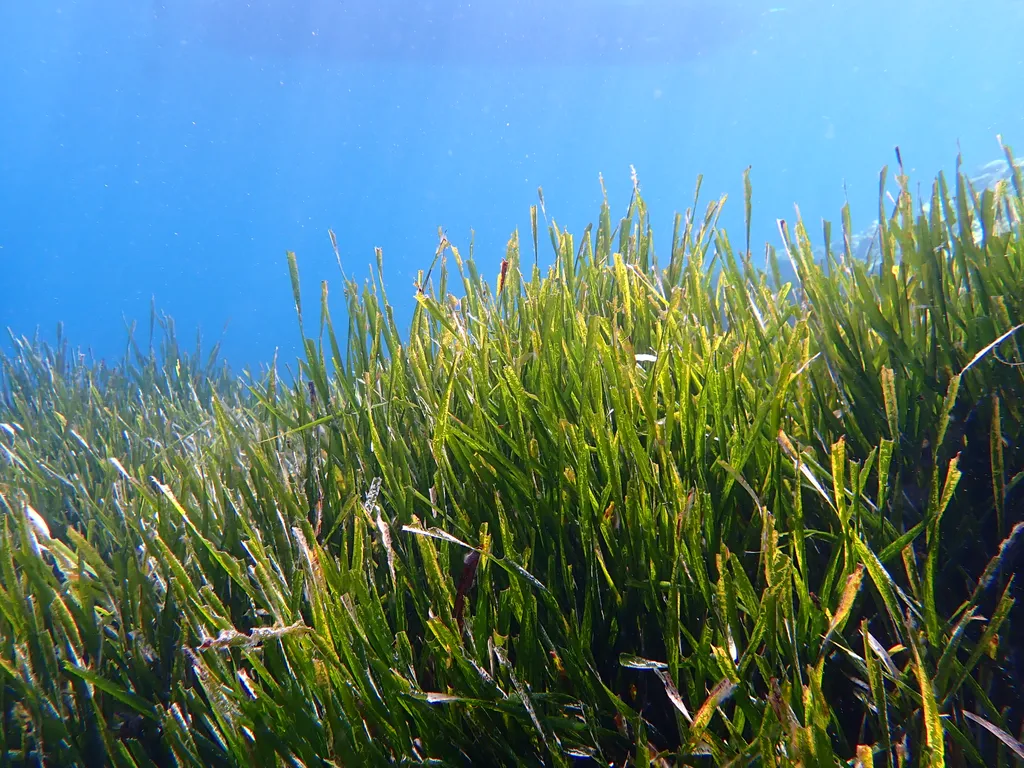

Photo by Frédéric Ducarme / CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

To a diver exploring shallow coastal waters, seagrass meadows might look like underwater lawns—gentle, swaying fields of green that seem almost too peaceful to be real. But these aren't just pretty decorations—they're flowering plants, the only true angiosperms that have fully adapted to life underwater. Seagrasses evolved from land plants around 70-100 million years ago, returning to the sea and developing remarkable adaptations: underwater pollination, salt tolerance, and the ability to photosynthesize while completely submerged. For divers, seagrass meadows are underwater forests that create entire ecosystems—nurseries for juvenile fish, feeding grounds for sea turtles and dugongs, hiding places for seahorses, and complex communities of epiphytes and invertebrates living on every blade. But they're also among the ocean's most threatened habitats, disappearing at alarming rates due to pollution, coastal development, and climate change. Understanding seagrass means understanding that sometimes the most important ecosystems are the ones we barely notice—the quiet meadows that support entire food webs, stabilize coastlines, and store massive amounts of carbon, all while looking deceptively simple.

🔬Classification

📏Physical Features

🌊Habitat Info

⚠️Safety & Conservation

Identification Guide

Photo by Lycaon via Wikimedia Commons

- Blade Structure: Long, ribbon-like or strap-shaped leaves (blades) rising from the substrate

- Root System: True roots and rhizomes (underground stems) anchoring in soft sediment

- Meadow Formation: Forms extensive beds or meadows, not individual plants

- Color: Bright to dark green when healthy; brown or yellow when stressed or dying

- Texture: Smooth, flexible blades that sway with currents

- Flowers: Small, inconspicuous flowers (often overlooked) for underwater pollination

- Epiphytes: Leaf surfaces often covered with algae, small invertebrates, or other organisms

- Habitat: Always on soft substrates (sand/mud), never on hard surfaces like rocks

- Depth: Most common in shallow water (1-10m) where light penetrates easily

- Associated Life: Look for seahorses, juvenile fish, sea turtles, and various invertebrates

Top 10 Fun Facts about Seagrass

Photo by Olivier Dugornay / CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

1. The Only True Marine Flowering Plants

Seagrasses are unique in the plant kingdom: they're the only flowering plants (angiosperms) that live completely submerged in saltwater. This distinction is crucial—while seaweeds are algae (simple organisms without true roots, stems, or flowers), seagrasses are true plants with all the complex structures of terrestrial vegetation, adapted for underwater life. They evolved from land plants around 70-100 million years ago, making a remarkable evolutionary journey back to the sea. This adaptation required solving numerous challenges: how to pollinate underwater (they developed thread-like pollen that floats on water currents), how to tolerate salt (specialized cells that excrete excess salt), and how to photosynthesize efficiently while submerged (thin, flexible leaves that maximize surface area). For divers, understanding this distinction helps explain why seagrass meadows feel so different from seaweed forests—they're not just different types of algae, but completely different kingdoms of life, with the complexity and ecological importance of terrestrial forests, just underwater.

2. The Blue Carbon Superstars

Seagrass meadows are among the ocean's most powerful carbon sinks, storing massive amounts of carbon in their biomass and, more importantly, in the sediments beneath them. While seagrasses cover less than 0.2% of the ocean floor, they're responsible for storing approximately 10-18% of the ocean's organic carbon burial. This "blue carbon" storage happens because seagrass roots and rhizomes trap organic matter in sediments, where it can remain for thousands of years without decomposing (due to low oxygen conditions). When seagrass meadows are destroyed, this stored carbon is released back into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change. For divers, this means that those peaceful green meadows aren't just pretty—they're actively fighting climate change by locking away carbon that would otherwise be in the atmosphere. Understanding this carbon storage capacity helps explain why seagrass conservation is so critical for climate mitigation, and why protecting these meadows is as important as protecting forests on land.

3. The Underwater Nursery

Seagrass meadows are among the ocean's most productive nursery habitats, providing shelter, food, and protection for countless juvenile marine animals. The dense blades create a three-dimensional maze that offers hiding places from predators, while the rich epiphyte communities on leaf surfaces provide food for small grazers. Juvenile fish of many species spend their early lives in seagrass beds, growing large enough to venture onto coral reefs or into deeper waters. Sea turtles graze on seagrass blades, while dugongs and manatees are specialized seagrass herbivores that depend entirely on these meadows for survival. Seahorses use seagrass blades as anchor points, their prehensile tails wrapped around individual blades. For divers, seagrass meadows are like underwater kindergartens—places where you'll find the smallest, most vulnerable stages of marine life, all protected by the gentle swaying of green blades. Understanding this nursery function helps explain why healthy seagrass meadows are essential for maintaining fish populations and why their destruction has cascading effects throughout marine ecosystems.

4. The Ancient Clones: Living for Millennia

Some seagrass meadows are among the oldest living organisms on Earth, with individual clones (genetically identical plants connected by rhizomes) that may be thousands of years old. The Mediterranean seagrass Posidonia oceanica has clones estimated to be over 100,000 years old, making them some of the oldest known living organisms. These ancient meadows grow extremely slowly, expanding through rhizome growth at rates of centimeters per year, but they can cover vast areas and persist for millennia if left undisturbed. This longevity is possible because seagrasses can reproduce both sexually (through flowers and seeds) and asexually (through rhizome extension), allowing successful clones to spread and dominate large areas. For divers, this means that when you're swimming through a seagrass meadow, you might be floating above an organism that's older than human civilization, a living connection to ancient oceans. Understanding this longevity helps explain why seagrass recovery from damage can take decades or centuries, and why protecting existing meadows is far more effective than trying to restore destroyed ones.

5. The Sediment Stabilizers: Coastline Protectors

Seagrass roots and rhizomes create dense networks that stabilize sediments and protect coastlines from erosion. The root systems bind sand and mud particles together, preventing them from being washed away by waves and currents. This stabilization is so effective that seagrass meadows can reduce wave energy by up to 50%, protecting shorelines from storm damage. The trapped sediments also improve water clarity by preventing particles from being suspended in the water column. For divers, this sediment stabilization means that seagrass meadows often have clearer water than surrounding areas, as particles settle out and remain trapped in the root systems. Understanding this stabilizing function helps explain why seagrass loss leads to increased coastal erosion and why these meadows are so valuable for protecting human infrastructure along coastlines. It's a reminder that sometimes the best coastal engineering comes from nature itself, and that protecting seagrass meadows is protecting our own shorelines.

6. The Water Purifiers: Natural Filtration Systems

Seagrass meadows act as natural water filtration systems, removing excess nutrients, pollutants, and suspended particles from the water column. The dense blade structure slows water flow, allowing particles to settle out, while the root systems absorb nutrients from both the water and sediments. This filtration is so effective that seagrass meadows can significantly improve water quality in coastal areas, reducing the impacts of nutrient pollution from land-based sources. Some seagrass species are particularly good at removing heavy metals and other toxins from the water, storing them in their tissues. For divers, this means that seagrass meadows often have cleaner, clearer water than surrounding areas, making them excellent places for photography and observation. Understanding this filtration function helps explain why seagrass loss is often associated with declining water quality and why these meadows are so important for maintaining healthy coastal ecosystems. It's a reminder that nature provides services that would be extremely expensive to replicate with human technology.

7. The Epiphyte Communities: Life on Every Blade

Seagrass blades support incredibly diverse epiphyte communities—algae, bacteria, small invertebrates, and other organisms that live attached to the leaf surfaces. These epiphytes can be so abundant that they form visible coatings on seagrass blades, sometimes making the blades look fuzzy or discolored. This epiphyte community is a complete ecosystem in itself, with grazers that feed on the epiphytes, predators that hunt the grazers, and complex food webs that depend on the seagrass structure. Some epiphytes are beneficial, providing additional food sources for seagrass-associated animals, while others can be harmful if they become too abundant and block light from reaching the seagrass. For divers, these epiphyte communities mean that seagrass meadows are microcosms of biodiversity—every blade is a tiny habitat supporting multiple species. Understanding these epiphyte communities helps explain why seagrass meadows are so rich in life and why they're excellent places for macro photography, with countless small creatures living on every surface.

8. The Underwater Pollination: A Unique Challenge

Seagrasses face a unique challenge: how to pollinate underwater. Unlike terrestrial plants that can rely on wind, insects, or birds to carry pollen, seagrasses must accomplish pollination in a dense, viscous medium (water) where pollen doesn't float freely. Different seagrass species have evolved various strategies: some produce thread-like pollen that floats on water currents, some release pollen in sticky masses that are carried by water movement, and some have flowers that rise to the surface for aerial pollination. The most remarkable adaptation is in species like Thalassia testudinum, which produces long, thread-like pollen that can drift for kilometers on water currents, finding female flowers through chance encounters. For divers, this underwater pollination means that seagrass flowers are often small and inconspicuous—easy to miss unless you're looking closely. Understanding this pollination challenge helps explain why seagrass reproduction can be slow and why sexual reproduction is often supplemented by the faster asexual reproduction through rhizome growth. It's a reminder that even the most fundamental biological processes must be completely reimagined when life moves from land to sea.

9. The Global Decline: An Unseen Crisis

Seagrass meadows are disappearing at alarming rates worldwide, with estimates suggesting a global loss of 1-1.5% per year—a rate that has accelerated in recent decades. Since the 1930s, it's estimated that nearly 30% of global seagrass coverage has been lost. The causes are numerous: coastal development that destroys habitat, pollution from land-based sources, boat anchors and propellers that tear up meadows, dredging operations, and climate change impacts like rising sea temperatures and ocean acidification. Some regions have lost over 90% of their historical seagrass coverage. This decline is particularly concerning because seagrasses are slow to recover—damaged meadows can take decades or even centuries to fully regenerate, if they recover at all. For divers, this means that the seagrass meadows we see today might be remnants of much larger historical meadows, and that future generations might see even less. Understanding this decline helps explain why seagrass conservation is so urgent and why every meadow matters. It's a reminder that some of the ocean's most important ecosystems are disappearing before our eyes, often without the public awareness that coral reefs receive.

10. The Economic Value: More Than Meets the Eye

Seagrass meadows provide enormous economic value through ecosystem services that are often taken for granted. They support fisheries by providing nursery habitat for commercially important fish species, protect coastlines from erosion (saving millions in infrastructure costs), improve water quality (reducing treatment costs), and store carbon (providing climate regulation services). Some estimates suggest that seagrass meadows provide ecosystem services worth thousands of dollars per hectare per year. They also support tourism and recreation—divers, snorkelers, and wildlife watchers are drawn to areas with healthy seagrass meadows. For divers, this economic value means that protecting seagrass isn't just an environmental issue—it's also an economic one, with real financial benefits from conservation. Understanding this economic value helps explain why seagrass restoration projects are increasingly being funded and why coastal communities are recognizing the importance of protecting these meadows. It's a reminder that nature provides services that have real economic value, and that destroying seagrass meadows isn't just an environmental loss—it's also an economic one.

Diving & Observation Notes

Photo by P.Lindgren / CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

🧭 Finding Seagrass Meadows

- Shallow Coastal Waters: Look in bays, lagoons, estuaries, and protected coastal areas (typically 1-10m depth).

- Soft Substrates: Always on sand or mud bottoms—never on hard surfaces like rocks or coral.

- Clear Water: Prefer areas with good light penetration and water clarity.

- Protected Areas: Often found in calm, sheltered waters away from strong wave action.

🤿 Behavior & Observation

- Swaying Motion: Watch blades sway gently with currents—creates mesmerizing underwater landscapes.

- Epiphyte Communities: Look closely at leaf surfaces for algae, small invertebrates, and other epiphytes.

- Associated Life: Search for seahorses, juvenile fish, sea turtles, dugongs, and various invertebrates.

- Root Systems: In clear water, observe the dense rhizome networks anchoring the meadow.

- Flowers: Look for small, inconspicuous flowers (often missed but important for reproduction).

📸 Photo Tips

- Wide-Angle: Capture sweeping meadows with shafts of light filtering through the blades.

- Macro Details: Focus on epiphytes, small invertebrates, and the intricate structures of individual blades.

- Motion Blur: Use slow shutter speeds to capture the gentle swaying motion of the grass.

- Natural Light: Best photography during early morning or late afternoon when light is soft and filtered.

- Contrast: Shoot against dark backgrounds or blue water to highlight the green blades.

⚠️ Safety & Ethics

- No Walking: Never stand on or walk through seagrass meadows—protect roots and rhizomes.

- Buoyancy Control: Maintain perfect buoyancy to avoid damaging blades or disturbing sediment.

- No Collection: Do not harvest or remove seagrass—many species are protected.

- Respect Habitat: Avoid anchoring in seagrass meadows; use mooring buoys when available.

- Minimal Disturbance: Approach slowly and observe from a distance—minimize your impact.

🌏 Best Locations

- Florida Keys (USA): Extensive Turtle Grass meadows with excellent visibility.

- Great Barrier Reef (Australia): Diverse seagrass species in lagoons and reef flats.

- Red Sea (Egypt): Seagrass beds near mangroves with interesting ecosystem interactions.

- Andaman Sea (Thailand): Sheltered lagoons with shallow seagrass and abundant juvenile fish.

- Mediterranean: Temperate seagrass meadows, including ancient Posidonia oceanica beds.

- Baja California (Mexico): Temperate seagrass species in clear, shallow waters.

Best Places to Dive with Seagrass

Anilao

Anilao, a small barangay in Batangas province just two hours south of Manila, is often called the macro capital of the Philippines. More than 50 dive sites fringe the coast and nearby islands, offering an intoxicating mix of coral‑covered pinnacles, muck slopes and blackwater encounters. Critter enthusiasts come for the legendary muck dives at Secret Bay and Anilao Pier, where mimic octopuses, blue‑ringed octopuses, wonderpus, seahorses, ghost pipefish, frogfish and dozens of nudibranch species lurk in the silt. Shallow reefs like Twin Rocks and Cathedral are covered in soft corals and teem with reef fish, while deeper sites such as Ligpo Island feature gorgonian‑covered walls and occasional drift. Because Anilao is so close to Manila and open year‑round, it’s the easiest place in the Philippines to squeeze in a quick diving getaway.

Lembeh

The Lembeh Strait in North Sulawesi has become famous as the muck‑diving capital of the world. At first glance its gently sloping seabed of black volcanic sand, rubble and discarded debris looks bleak. Look closer and it is teeming with weird and wonderful life: hairy and painted frogfish, flamboyant cuttlefish, mimic and blue‑ringed octopuses, ornate ghost pipefish, tiny seahorses, shrimp, crabs and a rainbow of nudibranchs. Most dives are shallow and calm with little current, making it an ideal playground for macro photographers. There are a few colourful reefs for a change of scenery, but Lembeh is all about searching the sand for critter treasures.

Maldives

Scattered across the Indian Ocean like strings of pearls, the Maldives’ 26 atolls encompass more than a thousand low‑lying islands, reefs and sandbanks. Beneath the turquoise surface are channels (kandus), pinnacles (thilas) and lagoons where powerful ocean currents sweep past colourful coral gardens. This nutrient‑rich flow attracts manta rays, whale sharks, reef sharks, schooling jacks, barracudas and every reef fish imaginable. Liveaboards and resort dive centres explore sites such as Okobe Thila and Kandooma Thila in the central atolls, manta cleaning stations in Baa and Ari, and shark‑filled channels like Fuvahmulah in the deep south. Diving here ranges from tranquil coral slopes to adrenalin‑fuelled drifts through current‑swept passes, making the Maldives a true pelagic playground.

Galapagos

The Galápagos Islands sit 1 000 km off mainland Ecuador and are famous for their remarkable biodiversity both above and below the water. Created by volcanic hot spots and washed by the converging Humboldt, Panama and Cromwell currents, these remote islands offer some of the most exhilarating diving on the planet. Liveaboard trips venture north to Darwin and Wolf islands, where swirling schools of scalloped hammerheads and hundreds of silky and Galápagos sharks patrol the drop‑offs. Other sites host oceanic manta rays, whale sharks, dolphins, marine iguanas, penguins and playful sea lions. Strong currents, cool upwellings and surge mean the dives are challenging but incredibly rewarding. On land you can explore lava fields, giant tortoise sanctuaries and blue‑footed booby colonies.

Komodo

Komodo National Park is a diver’s paradise full of marine diversity: expect healthy coral gardens, reef sharks, giant trevallies, countless schools of fish, and frequent manta ray sightings at sites like Manta Point and Batu Bolong. Drift dives and dramatic reef structures add excitement, while both macro lovers and big-fish fans will find plenty to love. Above water, the wild Komodo dragons roam, giving a touch of prehistoric wonder to the whole trip.

Palau

Rising out of the western Pacific at the meeting point of two great oceans, Palau is an archipelago of more than 500 jungle‑cloaked islands and limestone rock pinnacles. Its barrier reef and scattered outcrops create caverns, walls, tunnels and channels where nutrient‑rich currents sweep in from the Philippine Sea. These flows feed carpets of hard and soft corals and attract vast schools of jacks, barracudas and snappers, as well as an impressive cast of pelagics. Grey reef and whitetip sharks parade along the legendary Blue Corner; manta rays glide back and forth through German Channel’s cleaning stations; and Ulong Channel offers a thrill‑ride drift over giant clams and lettuce corals. Between dives you can snorkel among non‑stinging jellyfish in Jellyfish Lake or explore WWII ship and plane wrecks covered in colourful sponges.

Raja Ampat

Raja Ampat, the “Four Kings,” is an archipelago of more than 1,500 islands at the edge of Indonesian West Papua. Its reefs sit in the heart of the Coral Triangle, where Pacific currents funnel nutrients into shallow seas and feed the world’s richest marine biodiversity. Diving here means gliding over colourful walls and coral gardens buzzing with more than 550 species of hard and soft corals and an estimated 1,500 fish species. You’ll meet blacktip and whitetip reef sharks on almost every dive, witness giant trevally and dogtooth tuna hunting schools of fusiliers, and encounter wobbegong “carpet” sharks, turtles, manta rays and dolphins. From cape pinnacles swarming with life to calm bays rich in macro critters, Raja Ampat offers endless variety. Above water, karst limestone islands and emerald lagoons provide spectacular scenery between dives.