Sponge

Porifera

Photo by Albert Kok at Dutch Wikipedia(Original text: Albert Kok) via Wikimedia Commons

To a diver, sponges might look like colorful, oddly-shaped rocks or strange underwater plants—static, simple, and perhaps not particularly interesting. But this first impression couldn't be more wrong. Sponges are among the most ancient animals on Earth, with a fossil record stretching back 600 million years, and they represent one of evolution's most successful experiments in simplicity. These aren't plants or rocks—they're animals, but animals so fundamentally different from everything else that they challenge our basic definitions of what an animal is. Sponges have no organs, no tissues, no nervous system, no digestive system, and no circulatory system. Yet they're incredibly successful, filtering thousands of liters of water per day, hosting complex communities of symbiotic microbes, and playing crucial roles in reef ecosystems. For divers, sponges are the colorful, porous structures that dot reef walls and provide hiding places for countless small creatures. But understanding sponges means understanding that you're looking at a living filtration system, a biological pump that's been perfecting its craft for hundreds of millions of years. They're the ocean's original water purifiers, and they've been doing their job longer than almost any other animal on Earth.

🔬Classification

📏Physical Features

🌊Habitat Info

⚠️Safety & Conservation

Identification Guide

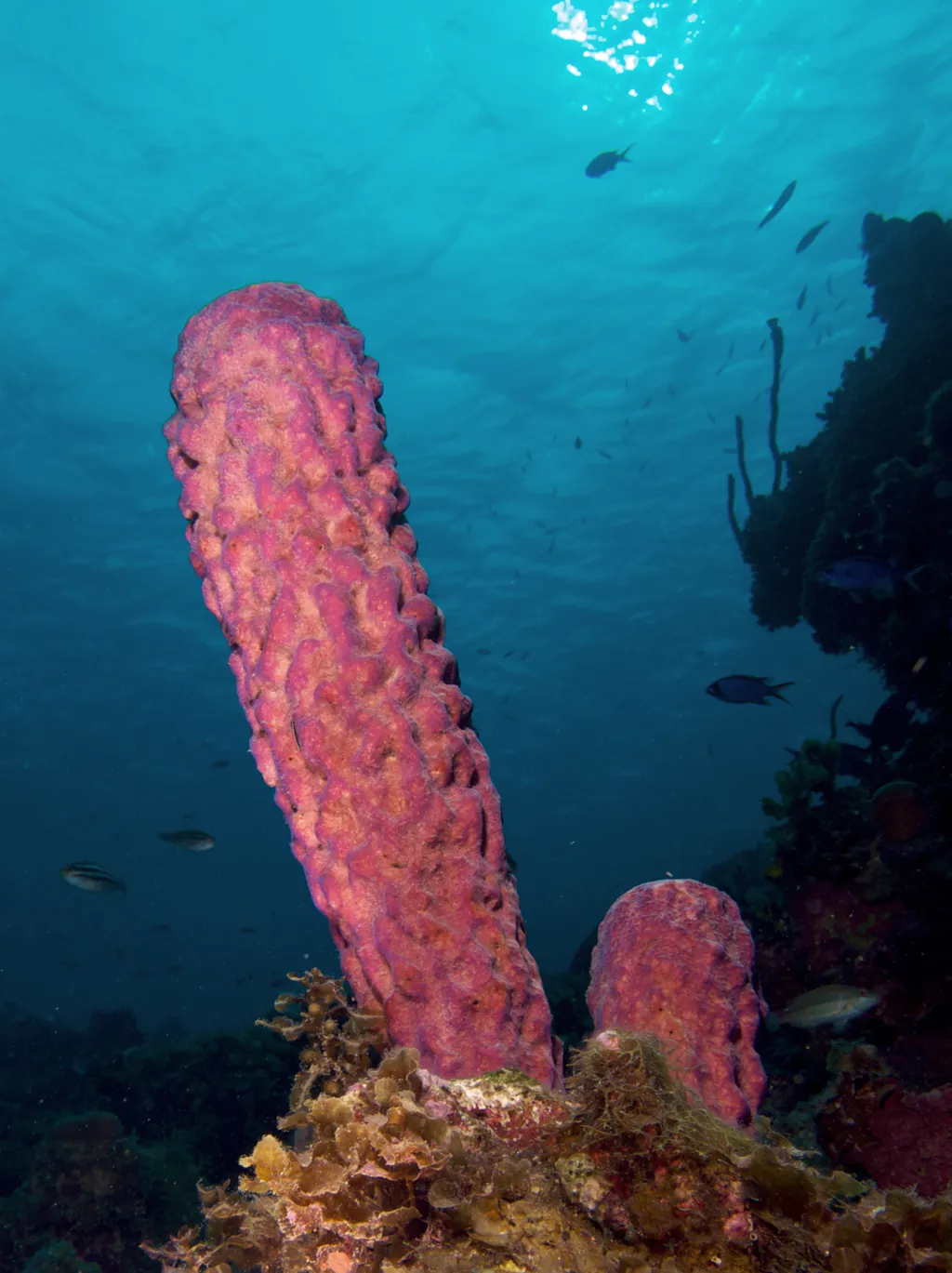

Photo by Nhobgood (talk) Nick Hobgood / CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

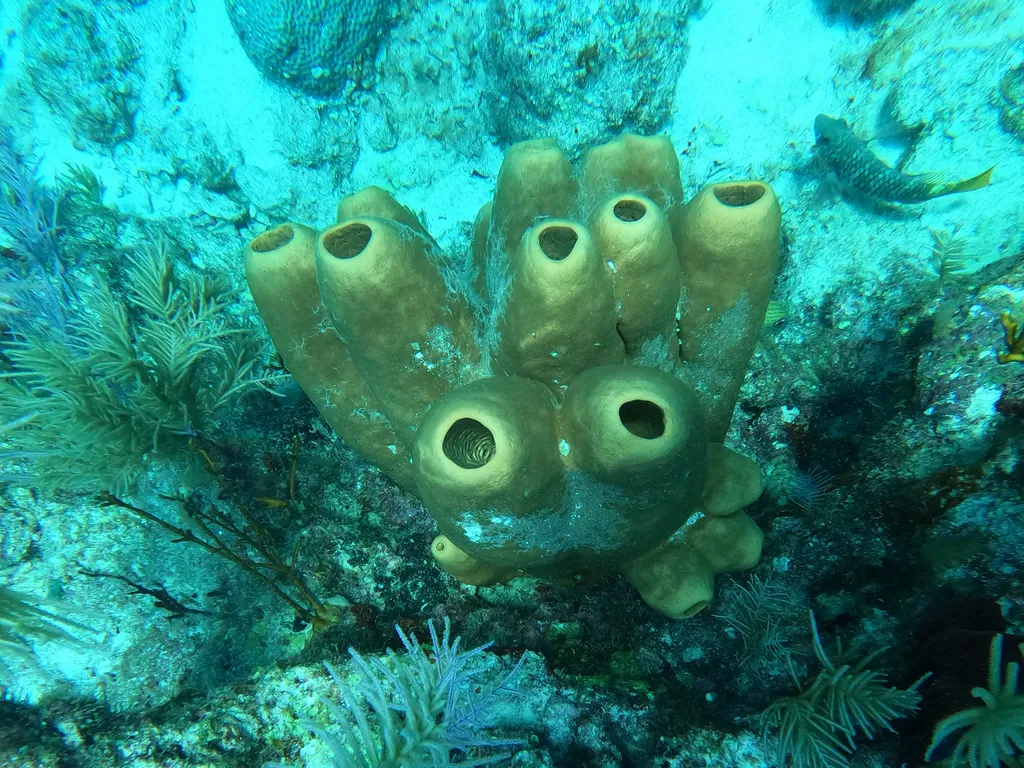

- Porous Surface: Look for numerous small openings (ostia) covering the surface—these are the intake pores

- Osculum: One or more larger openings (oscula) where water exits—often visible as distinct holes

- Texture: Soft and spongy (hence the name), but can vary from very soft to quite firm

- Shape Variety:

- Encrusting: Flat sheets covering rocks or reef surfaces

- Massive: Large, blocky or rounded forms

- Branching: Tree-like or bush-like structures

- Vase/Tube: Cup-shaped or tubular forms

- Barrel: Large barrel-shaped (especially in deep water)

- Color: Often bright and vibrant; can fade when exposed to air or strong light

- No Polyp Structure: Unlike corals, no visible polyps or tentacles

- Spicules: Microscopic skeletal elements—may feel slightly rough or grainy

- Water Flow: Observe water being drawn in through ostia and expelled through oscula

Top 10 Fun Facts about Sponge

Photo by Jstuby / CC0 via Wikimedia Commons

1. The Simplest Animals: No Organs, No Problem

Sponges challenge everything we think we know about what makes an animal an animal. They have no true organs, no tissues, no nervous system, no digestive system, and no circulatory system. Yet they're classified as animals because they're multicellular, heterotrophic (they eat other organisms), and have specialized cells. Instead of organs, sponges are essentially colonies of specialized cells working together. The basic body plan is a simple tube or sac with thousands of tiny pores (ostia) for water intake and one or more larger openings (oscula) for water exit. Water flows through the sponge continuously, driven by specialized cells called choanocytes (collar cells) that beat their flagella to create currents. These choanocytes also capture food particles from the water, making them both the pump and the filter. It's an incredibly efficient system: a single sponge can filter thousands of liters of water per day, removing bacteria, plankton, and organic particles. This simplicity is actually a strength—sponges have been perfecting this basic design for 600 million years, and it works so well that they've colonized virtually every marine environment on Earth, from shallow tropical reefs to the deepest ocean trenches. For divers, understanding this simplicity helps explain why sponges look so different from other reef animals—they're operating on a completely different biological principle.

2. The Choanocyte Revolution: Nature's Most Efficient Pump

The secret to a sponge's success lies in a single type of cell: the choanocyte (collar cell). These cells are the engine that powers the entire sponge. Each choanocyte has a collar of microvilli surrounding a single flagellum—think of it as a tiny, living water pump. The flagellum beats rhythmically, creating a current that draws water through the sponge's body. The collar acts as a filter, trapping food particles as water flows past. It's an elegant solution: one cell type does both the pumping and the filtering. But here's what makes choanocytes truly remarkable: they're almost identical to the cells found in choanoflagellates, single-celled protists that are the closest living relatives to all animals. This similarity suggests that choanocytes represent an ancient cell type that existed before animals evolved, and that sponges may have evolved from choanoflagellate-like ancestors. In other words, the cells that power sponges today are essentially the same cells that existed 600 million years ago, making choanocytes one of the most ancient and successful cell types in the animal kingdom. For divers, this means that every time you see a sponge filtering water, you're watching a biological process that's been running continuously for hundreds of millions of years—a living connection to the very origins of animal life.

3. The Sponge Loop: Recycling the Ocean's Carbon

Sponges play a crucial but often overlooked role in reef ecosystems through something called the "sponge loop"—a process that recycles dissolved organic matter (DOM) back into the food web. Here's how it works: when corals, algae, and other reef organisms produce organic matter, much of it dissolves into the water as DOM, which is too small for most animals to eat. Sponges, however, can filter and consume this DOM, along with bacteria and other tiny particles. They then convert this material into larger particles (detritus) that other reef animals can eat. Essentially, sponges are biological recyclers, taking waste products that would otherwise be lost and turning them back into food for the ecosystem. This process is so important that in some reef systems, sponges may process more carbon than corals do. The sponge loop helps explain why reefs with healthy sponge populations are often more productive and support more biodiversity. For divers, this means that those colorful sponges on the reef wall aren't just pretty decorations—they're active participants in keeping the reef ecosystem healthy and productive. Understanding the sponge loop helps us appreciate that reef ecosystems are more complex and interconnected than they might appear at first glance.

4. The Microbial Metropolis: Sponges as Living Cities

A sponge isn't just a sponge—it's a living city hosting a diverse community of microorganisms. Scientists have discovered that up to 40% of a sponge's volume can be made up of symbiotic bacteria, archaea, fungi, and other microbes. These microorganisms aren't just passengers—they're active partners in the sponge's survival. Some microbes help with digestion, breaking down complex organic compounds that the sponge can't process alone. Others produce defensive chemicals that protect the sponge from predators and competitors. Some even perform photosynthesis, providing the sponge with additional energy. The relationship is so intimate that many sponge species have specific microbial communities that are unique to that species—like a fingerprint of bacteria. Scientists are discovering that these microbial partnerships may be crucial for sponge health, and that environmental stress can disrupt these communities, leading to disease or death. The diversity is staggering: a single sponge can host hundreds of different microbial species, creating one of the most complex microbial ecosystems in the ocean. For divers, this means that when you look at a sponge, you're actually looking at a complex, multi-species community working together—a biological partnership that's been evolving for millions of years. Understanding this microbial dimension helps explain why sponges are so successful and why they're so important to reef ecosystems.

5. The Spicule Skeleton: Glass and Stone Architecture

Sponges may be soft, but they're not without structure. Their bodies are supported by spicules—microscopic skeletal elements made of either silica (glass) or calcium carbonate (stone). These spicules come in an astonishing variety of shapes: stars, needles, anchors, clubs, and intricate geometric forms. Each species has its own characteristic spicule shape, and scientists use these microscopic structures to identify sponge species—it's like using architectural blueprints to identify buildings. The spicules are embedded throughout the sponge's body, providing structural support and defense. Some spicules are sharp enough to deter predators, while others form complex networks that give the sponge its shape. In some deep-sea sponges, the spicules fuse together to form a rigid glass skeleton—these are the "glass sponges" (Hexactinellida) that can form massive, intricate structures. The largest glass sponges can be several meters tall and live for hundreds of years. For divers, spicules explain why some sponges feel slightly rough or grainy when touched—you're feeling millions of tiny skeletal elements working together. Understanding spicules helps us appreciate that even the softest-looking sponges have intricate internal architecture, a hidden complexity that's only visible under a microscope.

6. The Regeneration Masters: Breaking to Multiply

Sponges are masters of regeneration, capable of recovering from damage that would kill most other animals. If you cut a sponge into pieces, each piece can regrow into a complete new sponge. This ability is so remarkable that scientists have been studying it for decades, hoping to unlock secrets that could help with human medicine. The secret lies in sponge cells' ability to dedifferentiate—to revert from specialized cells back to stem-like cells that can then become any cell type needed. This is essentially biological time travel: cells that have committed to being one thing can go back and become something else entirely. Sponges use this ability not just for repair, but also for reproduction. Many species reproduce asexually through fragmentation—a piece breaks off, settles somewhere new, and grows into a new individual. Some freshwater sponges can even produce gemmules—dormant, encapsulated structures that can survive harsh conditions like freezing or drying out, then hatch when conditions improve. This regenerative ability makes sponges incredibly resilient and helps explain why they've been so successful for so long. For divers, this resilience means that sponges can recover from physical damage relatively quickly, though it's still important to avoid touching or damaging them, as recovery takes time and energy.

7. The Carnivorous Exception: Sponges That Hunt

While most sponges are filter feeders, a few species have taken a completely different approach: they're carnivorous predators that actively hunt and capture small animals. These predatory sponges, found primarily in deep, nutrient-poor waters, have evolved specialized structures to catch prey. Instead of the typical filter-feeding system, they have hook-like spicules or sticky filaments that snag small crustaceans and other animals that brush against them. Once caught, the prey is slowly digested by specialized cells. This predatory lifestyle is an adaptation to environments where there isn't enough plankton to support filter feeding—the deep sea, where food is scarce and competition is fierce. The discovery of carnivorous sponges surprised scientists, as it challenged the long-held assumption that all sponges were passive filter feeders. These predatory species represent one of evolution's most creative solutions to the problem of survival in extreme environments. For divers, carnivorous sponges are rarely encountered (they live in deep water), but they're a reminder that sponges are more diverse and adaptable than we might think. Understanding this diversity helps us appreciate that even within a single phylum, evolution can produce radically different solutions to the same basic problem: how to get food.

8. The Bioeroders: Sponges That Eat Rock

Some sponges have developed a unique and somewhat destructive talent: they can bore into and dissolve calcium carbonate, including coral skeletons and limestone rocks. These "boring sponges" (like species in the genus Cliona) use special cells that secrete acid to dissolve the substrate, creating networks of tunnels and chambers inside the rock or coral. While this might sound destructive, boring sponges actually play an important ecological role. They help break down dead coral skeletons, recycling calcium carbonate back into the ecosystem. They also create habitat—the tunnels and chambers they create provide homes for countless small organisms. However, when boring sponges attack living corals, they can cause significant damage, weakening the coral skeleton and making it more vulnerable to breakage. Scientists are studying how climate change and ocean acidification might affect boring sponge activity, as these processes could make it easier for sponges to dissolve calcium carbonate. For divers, boring sponges are often visible as colorful patches on coral surfaces or as networks of holes in dead coral. Understanding bioerosion helps us appreciate that reef ecosystems are dynamic, with constant processes of building and breaking down happening simultaneously. The same processes that create reefs also destroy them, and sponges are active participants in both.

9. The Chemical Factories: Medicine from the Sea

Sponges are among the ocean's most prolific producers of bioactive compounds—chemicals that have potential medical applications. Scientists have discovered hundreds of compounds from sponges that show promise for treating cancer, bacterial infections, inflammation, and other diseases. Some of these compounds are so potent that they're being developed into pharmaceuticals. For example, compounds from Caribbean sponges have been used to develop drugs for treating cancer and viral infections. The reason sponges produce so many defensive chemicals is that they can't run away from predators—they're stuck in one place, so they've evolved chemical warfare instead. These compounds deter predators, prevent other organisms from settling too close, and protect against disease. The diversity of these chemicals is staggering: different sponge species produce different compounds, and even individuals of the same species can produce different chemicals depending on their environment and the threats they face. Scientists are constantly discovering new compounds from sponges, making them one of the most promising sources of new medicines. For divers, this means that those colorful sponges on the reef might one day contribute to saving human lives. Understanding this pharmaceutical potential helps us appreciate that protecting sponge biodiversity isn't just about preserving pretty reef decorations—it's about preserving potential sources of life-saving medicines.

10. The Ancient Survivors: 600 Million Years of Success

Sponges have been around for a staggeringly long time—their fossil record extends back to at least 600 million years ago, making them among the oldest animals on Earth. They've survived every mass extinction event, including the one that killed the dinosaurs, and they've colonized virtually every marine environment from shallow tropical reefs to the deepest ocean trenches. This longevity isn't just a matter of luck—it's a testament to the success of their simple but effective design. The basic sponge body plan has remained largely unchanged for hundreds of millions of years because it works so well. Sponges can survive in conditions that would kill most other animals: extreme depths, cold temperatures, low oxygen, high pressure. Some species can even survive being frozen or dried out. This resilience has allowed sponges to persist through environmental changes that have wiped out countless other species. For divers, understanding this ancient history means that when you see a sponge, you're looking at a living fossil—an animal that has remained essentially unchanged while the world around it has transformed completely. Sponges are a window into the distant past, a reminder of what animal life looked like before complexity evolved. They're living proof that sometimes the simplest solutions are the most enduring.

Diving & Observation Notes

Photo by Nhobgood Nick Hobgood / CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

🧭 Finding Sponges

- Reef Walls & Slopes: Look on vertical walls, overhangs, and reef slopes—sponges prefer areas with good water flow.

- Caves & Crevices: Often found in shaded areas, caves, and crevices where they're protected from direct sunlight.

- Hard Substrates: Attached to rocks, dead coral, or reef framework—rarely on soft sand.

- Depth Range: Found from shallow reef flats (1-2m) to deep walls (40m+), with some species in very deep water.

🤿 Behavior & Observation

- Water Flow: Observe water being drawn in through ostia (small pores) and expelled through oscula (larger openings).

- Color Changes: Some sponges change color when exposed to air or strong light—observe natural underwater colors.

- Associated Life: Look for small fish, shrimp, and other creatures hiding inside or around sponges.

- Response to Touch: Some sponges may close oscula when disturbed—observe but don't touch.

📸 Photo Tips

- Macro Details: Focus on ostia and oscula patterns—reveals the intricate pore structure.

- Wide-Angle: Capture entire sponge colonies with surrounding reef life for context.

- Color Accuracy: Use natural light or proper white balance—sponge colors can be vibrant and photogenic.

- Texture: Side lighting helps reveal the sponge's surface texture and structure.

- Associated Life: Include small creatures using sponges as habitat in your compositions.

⚠️ Safety & Ethics

- No Touch: Never touch sponges—they're fragile and can be damaged easily.

- Buoyancy Control: Maintain perfect buoyancy to avoid accidental contact.

- No Collection: Do not collect sponges—many are protected and play important ecological roles.

- Respect Filtering: Don't block oscula or disturb water flow—sponges are actively filtering.

- Avoid Sediment: Don't kick up sediment that could clog sponge pores.

🌏 Best Locations

- Raja Ampat (Indonesia): Incredible diversity of sponge species and forms.

- Palau: Pristine reefs with healthy sponge populations.

- Red Sea: Unique sponge species adapted to high salinity.

- Caribbean: Classic sponge habitats with diverse species.

- Great Barrier Reef: Diverse sponge communities on outer reef walls.

- Galapagos: Unique sponge species in nutrient-rich waters.

Best Places to Dive with Sponge

Raja Ampat

Raja Ampat, the “Four Kings,” is an archipelago of more than 1,500 islands at the edge of Indonesian West Papua. Its reefs sit in the heart of the Coral Triangle, where Pacific currents funnel nutrients into shallow seas and feed the world’s richest marine biodiversity. Diving here means gliding over colourful walls and coral gardens buzzing with more than 550 species of hard and soft corals and an estimated 1,500 fish species. You’ll meet blacktip and whitetip reef sharks on almost every dive, witness giant trevally and dogtooth tuna hunting schools of fusiliers, and encounter wobbegong “carpet” sharks, turtles, manta rays and dolphins. From cape pinnacles swarming with life to calm bays rich in macro critters, Raja Ampat offers endless variety. Above water, karst limestone islands and emerald lagoons provide spectacular scenery between dives.

Palau

Rising out of the western Pacific at the meeting point of two great oceans, Palau is an archipelago of more than 500 jungle‑cloaked islands and limestone rock pinnacles. Its barrier reef and scattered outcrops create caverns, walls, tunnels and channels where nutrient‑rich currents sweep in from the Philippine Sea. These flows feed carpets of hard and soft corals and attract vast schools of jacks, barracudas and snappers, as well as an impressive cast of pelagics. Grey reef and whitetip sharks parade along the legendary Blue Corner; manta rays glide back and forth through German Channel’s cleaning stations; and Ulong Channel offers a thrill‑ride drift over giant clams and lettuce corals. Between dives you can snorkel among non‑stinging jellyfish in Jellyfish Lake or explore WWII ship and plane wrecks covered in colourful sponges.

Maldives

Scattered across the Indian Ocean like strings of pearls, the Maldives’ 26 atolls encompass more than a thousand low‑lying islands, reefs and sandbanks. Beneath the turquoise surface are channels (kandus), pinnacles (thilas) and lagoons where powerful ocean currents sweep past colourful coral gardens. This nutrient‑rich flow attracts manta rays, whale sharks, reef sharks, schooling jacks, barracudas and every reef fish imaginable. Liveaboards and resort dive centres explore sites such as Okobe Thila and Kandooma Thila in the central atolls, manta cleaning stations in Baa and Ari, and shark‑filled channels like Fuvahmulah in the deep south. Diving here ranges from tranquil coral slopes to adrenalin‑fuelled drifts through current‑swept passes, making the Maldives a true pelagic playground.

Komodo

Komodo National Park is a diver’s paradise full of marine diversity: expect healthy coral gardens, reef sharks, giant trevallies, countless schools of fish, and frequent manta ray sightings at sites like Manta Point and Batu Bolong. Drift dives and dramatic reef structures add excitement, while both macro lovers and big-fish fans will find plenty to love. Above water, the wild Komodo dragons roam, giving a touch of prehistoric wonder to the whole trip.

Phuket

Phuket is Thailand’s largest island and a gateway to the Andaman Sea’s best diving. While its beaches draw sun‑seekers, just offshore you’ll find coral slopes, granite pinnacles, dramatic walls and an intriguing shipwreck teeming with life. The nearby Racha islands offer year‑round clear water and easy dives, while to the east the King Cruiser ferry wreck, Shark Point, Anemone Reef and Koh Doc Mai deliver deeper currents, leopard sharks and superb soft corals. With a busy international airport and plenty of dive centres, Phuket is a convenient base for day trips and liveaboards further afield.

Similan

The Similan Islands are an archipelago of nine granite islands in the Andaman Sea off Thailand’s west coast, protected as part of Mu Ko Similan National Park. Underwater you’ll find dramatic boulder formations, swim‑throughs, coral gardens and drop‑offs teeming with life. Manta rays and whale sharks cruise by at sites like Richelieu Rock and Koh Tachai, while reef sharks, leopard sharks, turtles and swarming schools of fusiliers and trevally are common. The park is only open from mid‑October to mid‑May, when calm seas and clear water make for world‑class liveaboard trips or speedboat day tours.

Anilao

Anilao, a small barangay in Batangas province just two hours south of Manila, is often called the macro capital of the Philippines. More than 50 dive sites fringe the coast and nearby islands, offering an intoxicating mix of coral‑covered pinnacles, muck slopes and blackwater encounters. Critter enthusiasts come for the legendary muck dives at Secret Bay and Anilao Pier, where mimic octopuses, blue‑ringed octopuses, wonderpus, seahorses, ghost pipefish, frogfish and dozens of nudibranch species lurk in the silt. Shallow reefs like Twin Rocks and Cathedral are covered in soft corals and teem with reef fish, while deeper sites such as Ligpo Island feature gorgonian‑covered walls and occasional drift. Because Anilao is so close to Manila and open year‑round, it’s the easiest place in the Philippines to squeeze in a quick diving getaway.

Lembeh

The Lembeh Strait in North Sulawesi has become famous as the muck‑diving capital of the world. At first glance its gently sloping seabed of black volcanic sand, rubble and discarded debris looks bleak. Look closer and it is teeming with weird and wonderful life: hairy and painted frogfish, flamboyant cuttlefish, mimic and blue‑ringed octopuses, ornate ghost pipefish, tiny seahorses, shrimp, crabs and a rainbow of nudibranchs. Most dives are shallow and calm with little current, making it an ideal playground for macro photographers. There are a few colourful reefs for a change of scenery, but Lembeh is all about searching the sand for critter treasures.

Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef stretches for more than 2,300 km along Australia’s Queensland coast and is Earth’s largest coral ecosystem. With over 2,900 individual reefs, hundreds of islands, and a staggering diversity of marine life, it’s a bucket‑list destination for divers. Outer reef walls, coral gardens and pinnacles support potato cod, giant trevallies, reef sharks, sea turtles, manta rays and even visiting dwarf minke and humpback whales. Divers can explore historic wrecks like the SS Yongala, drift along the coral‑clad walls of Osprey Reef or mingle with friendly cod at Cod Hole. Whether you’re a beginner on a day trip from Cairns or an experienced diver on a remote liveaboard, the Great Barrier Reef offers unforgettable underwater adventures.

Galapagos

The Galápagos Islands sit 1 000 km off mainland Ecuador and are famous for their remarkable biodiversity both above and below the water. Created by volcanic hot spots and washed by the converging Humboldt, Panama and Cromwell currents, these remote islands offer some of the most exhilarating diving on the planet. Liveaboard trips venture north to Darwin and Wolf islands, where swirling schools of scalloped hammerheads and hundreds of silky and Galápagos sharks patrol the drop‑offs. Other sites host oceanic manta rays, whale sharks, dolphins, marine iguanas, penguins and playful sea lions. Strong currents, cool upwellings and surge mean the dives are challenging but incredibly rewarding. On land you can explore lava fields, giant tortoise sanctuaries and blue‑footed booby colonies.